Lifestyle

Frieze Masters Seoul 2024: Simply Irresistible

The hits – historical and contemporary – keep coming at Frieze Masters Seoul 2024.

Outstanding.” So enthuses Frieze Masters director Nathan Clements-Gillespie on the now three-year relationship between his fair and Seoul, currently the world’s most dynamic art city, one month before this year’s Frieze Seoul (and Frieze Masters Seoul), on September 4 -7. His excitement is palpable. “I don’t think any one of us – in fact, nobody – could have foreseen the unbelievable reception that Frieze Seoul received. Just the mutual joy and excitement with which Frieze and Seoul have taken to one another. It has been outstanding.”

So positive in fact, that, this edition of Frieze Masters Seoul sees the much-increased presence of galleries operating across the Asian region, including first-time participants Asia Art Center (Taipei and Beijing), DAG (New Delhi), Liang Gallery (Taipei), Mizoe Art Gallery (Japan), Galerie du Monde (Hong Kong) and Gallery Shilla (Seoul), participating alongside returning exhibitors Gana Art (Japan), Hakgojae Gallery (Seoul) and Tokyo Gallery + BTAP (Japan). Additionally, Frieze Masters participants will include dealers of 20th-century American works through Castelli Gallery and ACA Galleries, and medieval manuscript specialists Les Enluminures (Paris) and Robilant + Voena (London), which focus on European work, in some cases more than 600 years old.

Clements-Gillespie is also abuzz at the cognoscenti level of collectors on his visits to South Korea. “It’s remarkable to see how interested, cultivated and experienced collectors are in Korea. They come to Frieze Seoul having really done their homework. And galleries take note of that. And especially for the dealers in historical art, they’ve been overwhelmed by the number of people engaged with it.”

All of which is makes perfect sense, as that’s what Frieze Masters is all about. It shows art throughout the ages in a contemporary perspective, everything from collectible objects to significant Old Masters, to the late 20th century. “The ambition for Frieze Masters in Asia is to show the best of historical art, of global historical art,” Clements-Gillespie says.

“If you think of some of the older art fairs in continental Europe, they’re lucky to have a handful of visitors a day. And it’s mainly older people. But what I’ve found refreshing is that in Seoul it’s been younger people, just scores of younger people.” And not just visitors but younger generation artists, too. “We’ve had many young artists come to Frieze Masters in Seoul, who say, ‘Wow, we’ve never seen this outside of a museum.’”

It’s the perfect validation for the Frieze Masters platform he explains. “When Frieze Masters was born 12 years ago, it was to show historical art in a contemporary context and it was borne out of the notion that artists look to historical art … and are inspired by historical art and want to talk about how historical art has inspired their own practice.”

And that can take many forms. In the West, Clements-Gillespie singles out a show Tracey Emin held at Galleria Lorcan O’Neill in Rome almost a decade ago, which featured a sketchbook she’d made of the city’s Madonnas and angels and sculptures; he references George Condo and William Kentridge discussing the influenc of historical art in their own practices during the Frieze Masters Talks programme, and perhaps most surprisingly of all, Marina Abramović. “She gave a most beautiful talk at Frieze Masters London a few years back, in which she said, ‘I recognise it may not seem obvious that I take inspiration from Eugène Delacroix, so I’ve put together a brief Powerpoint to show where you can see the result of that in my own practice.’”

It’s notable too – though not part of Frieze Masters Seoul – that the current It-girl of British art, Louise Giovanelli, who’s trending in the contemporary art world, revisits religious work from the Renaissance

by singling out fragments from larger masterpieces for her own canvases. Effectively she’s re-Renaissancing the Classics into “what’s-old-is-new” contemporary must-haves, which she infuses with her gilt-edged, rapturous and glossy POV vibe. And Loewe Foundation Craft Prize-winner Korean artist Dahye Jeong, who makes innovative, elegant horsehair baskets, samples ancient Military headwear and armour worn by Koreans during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

Thus, Frieze Masters has become a platform where all art, irrespective of its period or geography or genre, takes centre stage.

“You can show a Socratic idol next to Picasso, and everything has room to breathe on an equal footing,” says Clements-Gillespie. “And, most importantly, you can show the ‘next gen’ that you don’t need to live in a dark castle with velvet walls to enjoy Old Masters. And if you do see an Old Master picture at Frieze Masters Seoul, you can imagine it in a contemporary penthouse.”

To what does he credit the sophistication of Seoul collectors and their spiralling apPetite for art appreciation and acquisition? “Every conversation I have in Seoul, around Seoul, is thoughtful, interesting and has weight. I sense that it’s testament to the rich heritage in Korea, both the country’s own artistic heritage, along with the number of art spaces and galleries, and the quality of the museums. There’s a culture of giving back to society through art and through museums,” he says.

In matters of historical art and South Korea, one of the themes of Frieze Masters Seoul is the iNFLuence of war, violence and destruction, and their effect on artistic production and the movement of artists thereafter. “To be working through the trauma of war – it can be such a rich source of inspiration,” says Clements-Gillespie. “I think it’s so important for an artist to be able to take something as traumatic as war and transform it into something new. One of the many things I admire about Korean culture is the use of the name Hyundai, which is ‘renewal’. I admire that after the Korean War, the name Hyundai was given

to so many things, be it the gallery, the Hyundai department store or Hyundai motor company. It’s this sense of renewal. Let’s not obsess over the past, but let’s use our past to make something new.”

Kim Young-Jin (born in 1946) and Kwok Hoon (born in 1941), showing through Gallery Shilla at Frieze Masters Seoul, are fine examples of such. They emerged in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950-1953)

to reappraise Korean Buddhist identity through modern experimental expression and an avant-garde creative thrust. While Kwok’s paintings depict traditional objects in repetition, Kim’s installations from the 2000s exemplify his ongoing exploration of shamanism and Buddhism, and recently featured in the exhibition Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960-70s, at The Guggenheim Museum, New York.

“They both used new and unexplored mediums in entirely original and different ways,” says Clements-Gillespie. “That’s what’s so special about art from the post-war period. And I think in Korea, having had this very fresh, raw and unsettled time, artists were even more inventive and imaginary in their use of materials and forms while working within the established principles of traditional artistic practice and making.”

In Korea, the latter half of the 20th century also saw the re-evaluation of Joseon porcelain from the 18th century, more popularly known as “moon jars”. These austere white vessels were the product of both warring and peaceful times during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) when, unable to secure cobalt during the Japanese invasion of Korea (1592-98) and Manchu invasions (1636-37), porcelain artists created the monochrome vessel as an alternative. And as the peninsula recovered from periods of turbulence, so its ceramic art followed, reaching new heights in the 18th century and later inspiring modern Korean artistic legends, such as Kim Whanki (1913-74), whose work is showing via Hakgojae Gallery at Frieze Masters Seoul.

While the name Hakgojae may not be household to those unfamiliar with Seoul, Clements-Gillespie describes the leading institution, opened in 1988, as a “must-see”. “I’m really glad that you’re speaking to the chairman, Chankyu Woo,” he says. “He’s an amazing person. Incredibly cultured. Very thoughtful. And just the breadth and the depth of historical material that they have is impressive and unique. They also have a very lovely gallery. And on the top floor is his calligraphy study. Because he’s a keen calligrapher himself.”

We seek out Woo and, before discussing Kim Whanki, he puts the Korean art world into context. “Hakgojae opened in 1988 during what could be considered the greatest boom since the founding of South Korea. At that time, the national income was less than US$10,000. Since then, it’s grown to exceed US$30,000. Along with this remarkable economic growth, the art market has also become the focus of the world’s attention. The exceptional individuality and passion of Koreans are astonishing. While maintaining this atmosphere, it’s now time to focus on substance. It’s time to contemplate Korea’s true identity and find ways for Korean art to receive global recognition and admiration for its unique characteristics.”

Certainly we tell him, that’s more than admirable in London, where Haegue Yang will show at the capital’s Hayward Gallery from October to February 2025, (Lee Bul was the last Korean female to show there

in 2019), while Mire Lee will install her artwork in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall from October. (Previously Korean-American Anika Yi showed there in 2022). In many respects, Yang and Lee stand on the shoulders of trailblazers like Nam June Paik, and Kim Whanki.

“Nam June Paik and Kim Whanki have left a significant mark on global contemporary art History beyond Korean art History,” Woo tells us. “Nam June Paik opened a new chapter in the global art scene with video art, becoming the first Korean artist to be honoured in global art History,” he says. “Kim Whanki [who worked in Seoul, Paris and New York] is a first-generation artist whose two-dimensional works have been recognised in global art History beyond Korean art History. His works draw inspiration from everyday life, deeply reflecting Korean sentiments, while also addressing macroscopic themes that everyone can relate to, such as the nature and divine providence of the universe. He’s gained global attention for modernising and poetically expressing traditional Korean aesthetics.”

As part of Frieze Masters Seoul, Hakgojae is showing three of Whanki’s works, including the eternal masterpiece Refugee Train (1951), a piece depicting the realities of the time during the Korean War, through repetitive abstract patterns. How does Woo assess the influence of Frieze and Frieze Masters in and on Seoul? “Frieze has opened the door for the Korean art market to leap from the periphery to the centre of the world. I believe it has provided Korean artists with an opportunity to think deeply and evaluate artists and works that will remain amid the flow of time.”

And what of his calligraphy? Will he ever show it to the world? No, it’s a private concern. “I took Oriental studies from a young age and naturally fell into calligraphy in my mid-teens. I enjoy expressing famous quotations from Eastern classics through calligraphy. Calligraphy is an act of self-expression. When the writing turns out as intended, it’s immensely enjoyable, but when it doesn’t, I take time to reflect on my inner self. Recently, I’ve been striving to write characters where the dots and strokes embody my inner strength and thoughts, rather than changing the form of the letters”.

Japan’s Tokyo Gallery + BTAP is another that’s championed the work of Korean and East Asian artists. Late Korean art legend Park Seo-Bo had seven shows with Tokyo Gallery between 1975 and 2016. In the ’60s, pioneering owner Takashi Yamamoto, who worked in an antique shop before starting his own gallery, was searching for new artists in Asia outside of Japan and found none in Southeast Asia. By chance, Korean artist Lee Ufan introduced Park Seo-Bo, in whom Yamamoto felt a strong personal interest. He admired Park’s deep conviction for Korean contemporary art, and visited Korea at Park’s invitation. And the rest is History. The gallery is also showing work by renowned geometric abstractionist Choi Myoung-Young, who last showed with them in 2000. Two of his works at Frieze Masters are from previous exhibitions with the gallery in 1984 and 2000. Also look out for the seductive Specious Rainbow of brother-and-sister duo SHIMURAbros, which examines new devices for visual experience.

Given the depth and expanse of art discoveries, both historical and contemporary on view at Frieze Masters Seoul, what’s on Clements-Gillespie’s to-do list while in the capital? “Speaking of contemporary artists inspired by historical art, I’d say make a beeline for Nicolas Party at Hoam Museum of Art, his first solo show in the country. I’m really, really interested to see that. Of course, Elmgreen & Dragset: Spaces at the Amore Pacific Museum of Art. Then there are selections from the Pinault Collection at SongEun Art Space.”

At which point he alerts us to manuscript dealer Les Enluminures, run by Dr Sandra Hindman, also part of Frieze Masters Seoul. “One thing that’s incredible about these objects is that they’ve been artworks, they’ve been objects of desire, of reverence and of artistry since they were made. And we have records of their price from the first time they were made. Many cost as much as, say, a townhouse in Britain or Antwerp at that time.” See The Lubbock Hours (“Use of Sarum”) with a Missal fragment dating from 1400, which is an illuminated manuscript on parchment with 19 full-page magnificent miniatures.

“What’s amazing is that over the course of 600 years, they’ve gained that value and that value has grown. They’re still the price of a townhouse,” Clements-Gillespie says. All are made with parchment, which is animal skin, and all the colours are precious stones; the gold is gold leaf, the blue is lapis lazuli. “All these colours are made with incredibly precious, valuable raw materials,” he tells us. “These were extraordinary creations from the very first moment they were made.” And each illumination, which is what illustrations are called in manuscripts, is performed by hand. “This was done by women. Nuns. They were devotional works, but they also raised important funds for religious establishments when they were made.” Golden moments indeed.

“And in terms of the fair, I think we’re so lucky to have with us somebody like Axel Vervoordt, who’s been so inspired by the art and the culture of South Korea, and who works with so many artists from South Korea. To me, it’s important to have them as part of Frieze Masters and so have this Western voice that’s got such a strong debt to South Korea and to South Korean art.”

Wherein the discoveries, both historic and contemporary at Frieze Masters Seoul, are infinite and simply irresistible.

(Header image: Ju Ming, Single Whip (1986))

-

Lifestyle3h ago

Lifestyle3h agoGladiator II' makes $106M in global box office | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle3h ago

Lifestyle3h agoA journey through the kitchen | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle6h ago

Lifestyle6h agoHow We Chose TIME’s 2024 Kid of the Year

-

Lifestyle7h ago

Lifestyle7h agoF1 NEWS: Hamilton Shows NO MERCY Towards Mercedes & Wolff After SABOTAGED Las Vegas GP!.cau

-

Lifestyle7h ago

Lifestyle7h agoMy Downstairs Neighbor Asked Me to Be Quieter at Night, but I Have Not Been Home for the past Week

-

Lifestyle9h ago

Lifestyle9h agoJin steps out of the BTS hive with 'Happy' | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle9h ago

Lifestyle9h agoContainers take over the wedding season | The Express Tribune

-

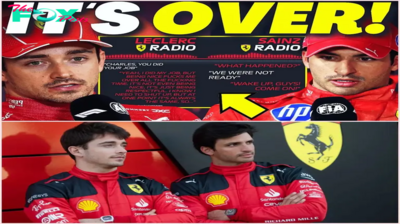

Lifestyle13h ago

Lifestyle13h agoF1 NEWS: Leclerc & Sainz FURIOUS At Ferrari After SHOCKING RADIO CONVERSATION GOT LEAKED At Las Vegas GP!.cau