Health

Medical debt affects much of America, but Colorado immigrants are hit especially hard

By Rae Ellen Bichell and Lindsey Toomer, KFF Health News and Colorado Newsline

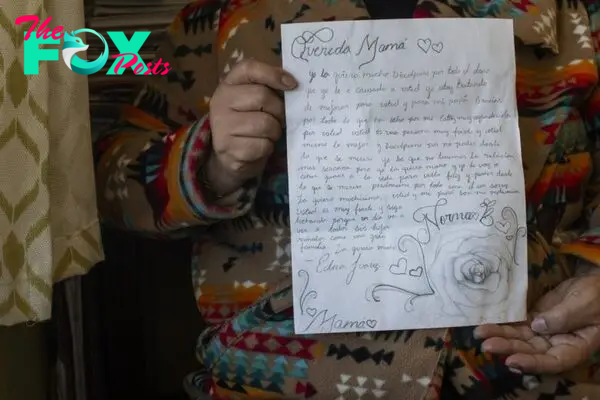

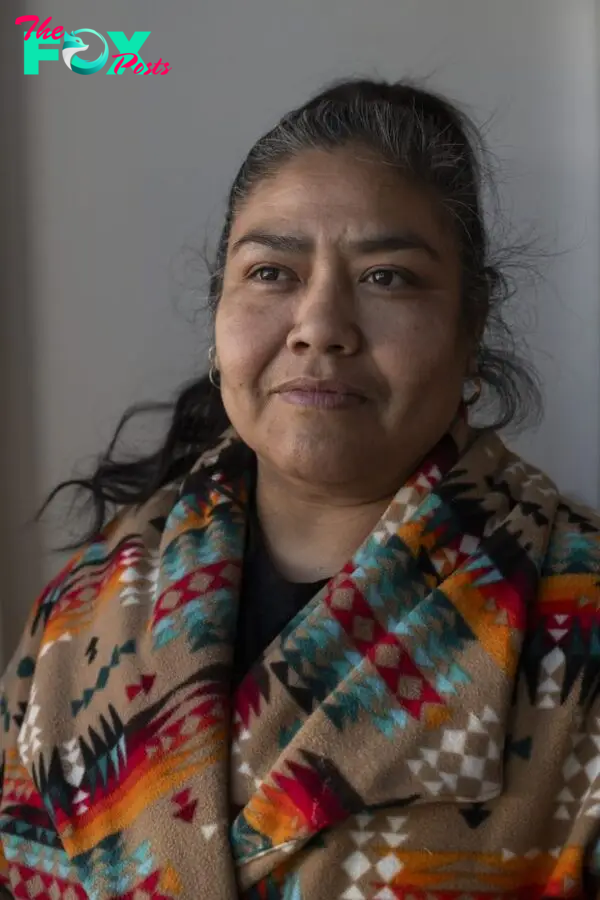

In February, Norma Brambila’s teenage daughter wrote her a letter she now carries in her purse. It is a drawing of a rose, and a note encouraging Brambila to “keep fighting” her sickness and reminding her she’d someday join her family in heaven.

Brambila, a community organizer who emigrated from Mexico a quarter-century ago, had only a sinus infection, but her children had never seen her so ill. “I was in bed for four days,” she said.

Lacking insurance, Brambila had avoided seeking care, hoping garlic and cinnamon would do the trick. But when she felt she could no longer breathe, she went to an emergency room. The $365 bill — enough to cover a week of groceries for her family — was more than she could afford, pushing her into debt. It also affected another decision she’d been weighing: whether to go to Mexico for surgery to remove the growth in her abdomen that she said is as big as a papaya.

Brambila lives in a southwestern Denver neighborhood called Westwood, a largely Hispanic, low-income community where many residents are immigrants. Westwood is also in a ZIP code, 80219, with some of the highest levels of medical debt in Colorado.

More than 1 in 5 adults there have historically had unpaid medical bills on their credit reports, more in line with West Virginia than the rest of Colorado, according to 2022 credit data analyzed by the nonprofit Urban Institute.

☀️ READ MORE

The $1.3 billion-plus problem: Explaining medical debt in Colorado using 7 charts

How doctors in Denver helped pioneer research on a new drug for food allergies

400 people with mental illness are sitting in Colorado jails. Some state lawmakers want to divert them to treatment instead.

The area’s struggles reflect a paradox about Colorado. The state’s overall medical debt burden is lower than most. But racial and ethnic disparities are wider.

The gap between the debt burden in ZIP codes where residents are primarily Hispanic and/or non-white and ZIP codes that are primarily non-Hispanic white is twice what it is nationally. (Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races.)

Medical debt in Colorado is also concentrated in ZIP codes with relatively high shares of immigrants, many of whom are from Mexico. The Urban Institute found that 19% of adults in these places had medical debt on their credit reports, compared with 11% in communities with fewer immigrants.

Nationwide, about 100 million people have some form of health care debt, according to a KFF Health News-NPR investigation. This includes not only unpaid bills that end up in collections, but also those being paid off through installment plans, credit cards, or other loans.

Racial and ethnic gaps in medical debt exist nearly everywhere, data shows. But Colorado’s divide — on par with South Carolina’s, according to the Urban Institute data — exists even though the state has some of the most extensive medical debt protections in the country.

The gap threatens to deepen long-standing inequalities, say patient and consumer advocates. And it underscores the need for more action to address medical debt.

“It exacerbates racial wealth gaps,” said Berneta Haynes, a senior attorney with the nonprofit National Consumer Law Center who co-authored a report on medical debt and racial disparities. Haynes said too many Colorado residents, especially residents of color, are still caught in a vicious cycle in which they forgo medical care to avoid bills, leading to worse Health and more debt.

Brambila said she has seen this cycle all too often around Westwood in her work as a community organizer. “I really would love to help people to pay their medical bills,” she said.

Health or debt?

Roxana Burciaga, who grew up in Westwood and works at Mi Casa Resource Center there, said she hears questions at least once a week about how to pay for medical care.

Medical debt is a “big, big, big topic in our community,” she said. People don’t understand what their insurance actually covers or can’t get appointments for preventive care that suit their work schedules, she said.

Many, like Brambila, skip preventive care to avoid the bills and end up in the emergency room.

Doctors and nurses say they see the strains, as well.

Amber Koch-Laking, a family physician at Denver Health’s Westwood Family Health Center, part of the city’s public Health system, said finances often come up in conversations with patients. Many patients try to get teleHealth appointments to avoid the cost of going in person.

-

Health12h ago

Health12h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health13h ago

Health13h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts