Lifestyle

Carsten Höller: The Artist Who Banned Ketchup

After making a name for himself with installations of giant hallucinogenic mushrooms and helter-skelter slides, experimental artist CARSTEN HÖLLER has moved into the realm of avant-garde cuisine. At the Asian debut of his Brutalisten concept in Seoul, he talks about starting a new movement and why painting is redundant.

Does the mind of Carsten Höller ever stop? It turns out it doesn’t. Although visitors to the conceptual artist’s shows are attuned to being pawns in his experimental art, he recently became the subject of his own test. “Not too long ago I spent six weeks alone at my home in Ghana [a Brutalist concrete structure in Cape Coast, four hours from Accra] and I didn’t speak to anybody. Apart from buying food, I had very little communication with other humans, mainly with the aim of finding out if the constant flow of thoughts stops if you don’t feed them by social invasion. And I can tell you they didn’t and probably never will.”

Speaking during Frieze Seoul week, where he’s brought his latest avant-garde cuisine concept as part of Porsche’s Art of Dreams exhibition (of which more later), he cautions, “Creativity isn’t just closing your eyes and doing nothing. It’s about selection. You need to train yourself to select the right things.”

That time alone in Ghana evidently proved a bountiful source of inspiration for his work. Even by Holler’s marvellously mad standards, the artist has had a busier year than most.

In March, he and fashion confidante and longtime collaborator Miuccia Prada took the third iteration of The Double Club to Los Angeles as part of Prada Mode. Continuing the exploration of duality in his works, Holler created a nightclub-cum-carnival inside a warehouse alongside fair rides created by Basquiat, Haring and Hockney for the now-closed 1980s Luna Luna amusement park.

Then he teased a forthcoming dream hotel project in collaboration with dream scientist Adam Haar Horowitz, with an installation at the Swiss Foundation Beyeler, inviting guests to nap or sleep overnight in the museum underneath spinning fungi, with the aim of eliciting dreams of flying with fly agaric mushrooms.

In July, he unveiled Doubt Staircase, a permanent stone and marble spiral stairway inside Venice’s Palazzo Diedo, built at a five-degree incline to disport people’s sense of proprioception. And last month he became the talk of the town at Paris Art Basel Week by erecting a three-metre-high aluminium red-capped mushroom sculpture in Place Vendôme. Named Giant Triple Mushroom, the Gagosian-presented sculpture represents a hybrid fungus combining the red top of the fly agaric, the net of the basket stinkhorn and the gills of the dove-coloured tricholoma. The aim, says Höller, was to position such a feat of nature, in dialogue with the man-made cultural evolution of the square.

Erecting a psychedelic shroom in incongruous contrast to the square’s Ritz Hotel and luxury boutiques is characteristic of Höller’s free-wheeling audacity. After all, he cites Sigmar Polke’s Higher beings coMMAnded: paint the upper right corner black! as the work that impacted him most. “It’s kind of a stupid painting, but it’s still interesting. To start with this brazen, slightly childish statement and deliver a bad work is actually quite a remarkable approach. I found it surprising to see things that artists could do, the ability to be so bold.”

Born in Belgium to German parents, Höller studied agricultural Science and worked as a research entomologist before becoming an artist in 1993. Often likened to a mad professor or lapsed scientist, his large-scale interactive works, frequently incorporating plants and Animals, explore human behaviour, doubt, perception and reality. To see Höller’s work is a disorienting living experience and occasionally requires visitors – or rather participants – to temporarily relinquish control; all in the name of art, bien sûr.

“I like to scare people and make them feel very uncomfortable,” he explains. “I’m more interested in taking down the middle ground, what we call the comfort zone. Probably we want to be there. But it’s more interesting to create a scenario where you live in two extremes at the same time. Maybe joy on the one side and fear on the other.”

Although he’s racked up an impressive oeuvre this year alone, to the layman Höller is best associated with his installation of five giant helter-skelter slides in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, or the now insta-famous Upside Down Mushroom Room (2000), the permanent installation of spinning fungi at Milan’s Prada Foundation that would make Alice in Wonderland blush.

Linked to the ’90s relational aesthetics movement, the artist was never drawn to the easel. “I don’t think it would be adequate to the times we live in for me to stand in front of a canvas and “express myself”. Who cares about me expressing myself on canvas? Canvas is kind of a dead medium. It doesn’t do anything except depict the status quo of somebody who’s decided this is now a finished painting. Actually, painting is rather irrelevant for the times we live in. And maybe that’s why I’m successful. I’m interested in things we could experience, so I see myself very much as an experiment.”

It’s this spirt of experimentation that’s led Höller to his next endeavour: food. Fished out of his running thoughts one morning, the artist had the idea of applying the tenets of Brutalist architecture to the plate, he promptly scribbled down the first draft of his 13-point Brutalist Kitchen Manifesto. To suMMArise: ingredients are used alone and only water and salt may be added, the use of hard-to-find or overlooked ingredients is encouraged, different ingredients aren’t allowed on the same plate and decoration is to be avoided. As for condiments? Think again.

“Often when I go to restaurants I think there’s too much stuff on my plate. I really don’t like that or this idea that you combine products to make something better than the product itself. It works, of course – there are some great dishes – but it’s also very nice to leave the product on its own and cook with the different parts to bring out a specific taste. So, it’s very much about that specificity.” For Höller the concept represents a natural human impulse. “We’re born as Brutalist eaters, our mother’s milk is essentially Brutalist”

I don’t think it would be adequate to the times we live in for me to stand in front of a canvas and “express myself”

Höller’s approach to cuisine is no different from that of art. “It’s about starting with an idea and implementing it in the best way you can,” he says. Enlisting his now head chef, Stefan Eriksson, to develop the concept, Brutalisten debuted via a series of pop-ups before moving to its permanent home in 2022, a 24-seat restaurant in Stockholm using local organic suppliers, line-caught fish and seasonal vegetables. The presence of Miuccia Prada and stylist Giovanna Battaglia Engelbert at the opening helped add to the venue’s cool cachet, while the interiors designed at a five-degree slant are classic Höller.

Bringing the concept to Seoul was an entirely new challenge. “Korea is a culture where you don’t prepare things on their own, like we do in our kitchen. It’s a lot of combination food.” Any hitches, however, weren’t evident to the 30 guests who sampled the nine-course Brutalisten menu, seated around a long metal table beneath a hanging knitted polystyrene sculpture by buzzy Korean artist Kwangho Lee.

The lunch, which opened with a plate with two brassica cabbage leaves, included a pumpkin course – the vegetable served raw, in seed, paste and oil form – as well as a mushroom plate, serving pan-fried oyster mushrooms, mushrooms cooked in smoked shiitake broth and button mushroom purée. There was a hint of apprehension around the Gomgukm Korean Cow course, which included the tongue, grilled heart, poached brain and broth of the bones of Hanwoo cow, but everything was consumed while managing to intrigue and impress both Asian and Western diners.

In general, Höller is happy with the concept’s reception. “It’s of interest not just to chefs, but also to people who like to eat because, they don’t want all this other stuff on their plate. It’s wrong, and it doesn’t do any good to the product.”

He’s even so bold as to float the possibility of a new global movement. “As an artist, it’s almost impossible to come up with a new artistic idea that would catch on. The last time that happened was maybe in the ’90s with relational aesthetics. But in the world of food it’s possible for me as an artist to have an idea that spreads on its own like a trend, almost creating a movement, and hopefully other people will pick it up too.”

(Hero Image: Giant Triple Mushroom (2024) in Place Vendôme, Paris. Courtesy of Gagosian)

-

Lifestyle17m ago

Lifestyle17m agoRECORD BREAKER: Brock Bowers Stuns Fans with a Historic Rookie NFL Season.Cau

-

Lifestyle5h ago

Lifestyle5h agoNFL HIGHLIGHT: Patriots’ Vederian Lowe Shocks with Epic “Thicc-Six” Touchdown—The 6-Foot-5, 315-Pound Star Steals the Show.Cau

-

Lifestyle5h ago

Lifestyle5h agoHEARTBREAKER: Bears Miss Game-Winning Field Goal at the Buzzer, Suffer Yet Another Defeat to the Packers.Cau

-

Lifestyle7h ago

Lifestyle7h agoMishi Khan cautions girls about rising risk of 'leaked videos' trend | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle12h ago

Lifestyle12h agoSalman Khan takes a swipe at Ashneer Grover's brand ambassador comment | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle12h ago

Lifestyle12h agoWATCH: Allu Arjun's film 'Pushpa 2' trailer unveiled | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle16h ago

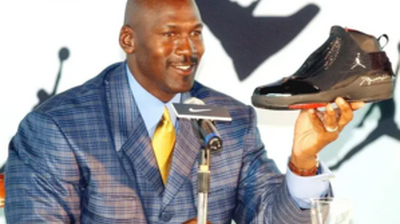

Lifestyle16h agoMichael Jordan Unveils Contract Behind Tragic Mishap of Iconic Release 12 Years Ago.Linh

-

Lifestyle17h ago

Lifestyle17h agoMCU's 'perfidious' witch | The Express Tribune