History

The Pro-Russia Conspiracy Theory That Almost Convinced New Englanders to Secede

GOP resistance to funding Ukraine’s war effort, along with the refusal by several Republicans to condemn Russian President Vladimir Putin for the death of opposition leader Alexei Navalny has been a clear sign that this is no longer the staunchly anti-Soviet, anti-Russia GOP of yesteryear. And it’s not just elected Republicans who are expressing affinity for the Russians. The admiration for Putin on the right borders on sycophancy — which was evident from conservative pundit Tucker Carlson’s softball interview with the Russian leader.

Yet, while this is a major turn away from the GOP of the 1980s, it’s not the first time in American History that radical conservatives have lionized a Russian autocrat. During the War of 1812, New England Federalists venerated Russian Tsar Alexander I. The similarities between the two stories reveal the potency of conspiracy theories in Politics, as well as the dangers of seeing Politics as a battle between good and evil.

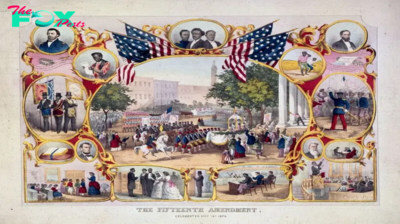

On March 25, 1813, Massachusetts politicians, merchants, and clergymen packed into King’s Chapel in Boston to thank God for inspiring Russia’s victory over French invaders. After a series of sermons, these conservatives reconvened at the Exchange Coffee House. The gathering spot was decorated with a transparency depicting Alexander I in military uniform while the Russian imperial anthem echoed through its halls. The dinner guests toasted in honor of Alexander, bestowing him with the epithets “the Great” and “the Deliverer of Europe.”

On its face, this celebration made no sense: after all, Russia was allied with Great Britain, which was currently at war with the U.S. But there was a crucial reason for the jubilation in the room, as explained by wealthy Boston merchant Harrison Gray Otis, who had organized the gathering. Otis proclaimed that the Russian Tsar’s victory had saved the U.S. from its “greatest danger” — French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Read More: Tucker Carlson and the Right's Long Love Affair with Dictators

The claim was striking given that British redcoats were currently occupying American territory. But it made sense if one understood the false conspiracy theory that had taken hold among Federalists during the previous two decades.

During the administrations of Democratic-Republican Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, New England Federalists had come to believe that the two were actually secret servants to the French Emperor. Newspapers, political pamphlets, and printed sermons spread the belief that the two Virginians sold America’s independence to Bonaparte to ensure their perPetual rule at the expense of New England.

While the theory was completely false, it proved powerful because it helped New Englanders make sense of cultural and political changes that appeared antithetical to their way of life. As the descendants of the Puritans and vanguards of the American Revolution, they had assumed that their region would steer the new nation’s development. Instead, Virginians came to dominate national politics and implement policies that ran counter to New England’s interests and traditions.

The conspiracy theory took root even before Jefferson assumed the presidency. In the 1790s, Jefferson, Madison, and their Democratic-Republican allies sought to remake U.S. culture by implementing the anti-aristocratic and democratic ideals of the French Revolution. This embrace of French radicalism undermined New England’s hierarchical society and persuaded Federalists that Jefferson and Madison were evil agents of Revolutionary France.

They saw the Democratic-Republicans’ affinity for France as a threat to another key pillar of New England society as well: Christianity. Atheism had driven the French Revolution and Bonaparte’s violent campaigns across Europe were spreading French atheism, or so the Federalists believed. His ambition for universal domination and his distribution of radical French ideals convinced New England clergymen that the French Emperor was the “Antichrist.”

When Jefferson and later Madison assumed the presidency, New Englanders feared that the two French agents would use the federal government to carry out Bonaparte’s orders.

Crucially, in 1807, Jefferson attempted to punish Great Britain for impressing American sailors by enacting a trade embargo against all foreign nations. The embargo did great damage to the New England economy and fanned the flames of the conspiracy theories swirling around the region. New England conservatives interpreted it as Jefferson working to advance Bonaparte’s grand ambitions to defeat Great Britain. Seeing the Virginians as puppets also convinced New Englanders that the War of 1812 was orchestrated by the French Emperor.

The rampant conspiracy theories so radicalized New Englanders that they contemplated separating from the U.S. during the war. New England newspapers and printed sermons warned readers to avoid supporting a war designed to benefit Bonaparte’s imperial ambitions and ruin New England’s prosperity. Radicals such as Boston judge Thomas Dawes concluded that secession was the only way to save New England from “the yoke of Bonaparte and Virginia.”

Moderate Federalists forestalled secession by organizing the Hartford Convention to address the region’s grievances. But the radicals’ hatred and fear of Bonaparte and the Democratic-Republicans had nonetheless fueled praise for Alexander I. Federalists lavished him with accolades in everything from sermons to Fourth of July celebrations. In their eyes, the Russian Czar symbolized a bulwark against French atheism and a protector of Christianity.

When news of Napoleon’s exile to Elba arrived in the summer of 1814, conservative Bostonians gathered once again to praise God for rescuing the U.S. and Europe. They expressed special gratitude to Alexander, “the great head of the Confederacy for the deliverance of Christendom,” and boasted that the Russian autocrat “will be always dear to every lover of national freedom.” The Federalists had mistakenly reasoned that Napoleon’s exile would expose his reign over the U.S. and thus force Madison to pursue peace with Great Britain.

Read More: How Putin Co-Opted the Republican Party

The conspiracy theories so animating New England Politics had reduced complex political and cultural changes to a simple narrative of good versus evil. They transformed elected officials like Jefferson and Madison into corrupt tyrants in the same category as Bonaparte. They also gave the Federalists a common cause with Great Britain and Russia — nations seemingly resisting the lure of the Antichrist.

Radicalized by conspiracy theories, New England conservatives worried about threats to America’s independence and representative government. Such fears led them to champion a Russian autocrat and radical ideas such as secession. Because the stakes were so high the Federalists overlooked the inherent contradiction in their desire to preserve their representative government and their admiration for a Russian autocrat.

There are many similarities between the far right’s admiration for Putin in 2024 and the Federalists’ love for Alexander in the 1810s. Like the Napoleonic conspiracy, modern far-right theories offer a clear story arc of good versus evil that helps their followers make sense of the cultural upheaval and increasing diversity in the U.S. They also drive the right to embrace the autocratic Putin. Instead, of seeing his repressive tactics as the antithesis of American democracy, they instead see him on the side of good in the battle against evil. Putin, in their view, is an anti-woke crusader fighting against the corrupt, irreligious West. Such false narratives also clarify why one American pastor predicted that the Russian dictator would expose Joe Biden’s and Barack Obama’s “evil plans” regarding the 2020 election.

Like Alexander I, Putin represents a misguided symbol for radicalized conservatives navigating cultural change and rampant conspiracy theories. The right’s admiration for him is a warning about the dangers of seeing politics as a battle between good and evil, and the perils of conspiracy theories. As it did in the 1810s, this sort of thinking can lead to radical action that poses a real threat to the republic.

Nicholas DiPucchio completed his doctorate in American history at Saint Louis University and currently works at Oakland University in Rochester, Mich. He is finishing up his book, Making Manifest Destiny: The Contingent Expansion of the Early American Republic.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

-

History1w ago

History1w agoWhy People Should Stop Comparing the U.S. to Weimar Germany

-

History1w ago

History1w agoFlorida’s History Shows That Crossing Voters on Abortion Has Consequences

-

History1w ago

History1w agoThe 1994 Campaign that Anticipated Trump’s Immigration Stance

-

History2w ago

History2w agoThe Kamala Harris ‘Opportunity Agenda for Black Men’ Might Be Good Politics, But History Reveals It Has Flaws

-

History2w ago

History2w agoLegacies of Slavery Across the Americas Still Shape Our Politics

-

History2w ago

History2w agoKamala Harris Is Dressing for the Presidency

-

History2w ago

History2w agoWhat Melania Trump’s Decision to Speak Out on Abortion Says About the GOP

-

History2w ago

History2w agoThe Long Global History of Ghosts