Health

New mRNA vaccine for deadly brain cancer triggers a strong immune response

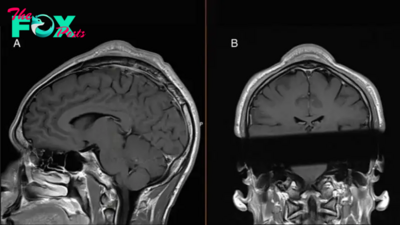

For the first time, scientists have tested a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine in a patient with a deadly form of brain cancer — and it triggered a strong immune response.

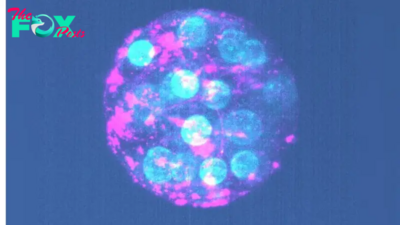

The vaccine, which was described in a study published on May 1 in the journal Cell, was created by extracting genetic material called RNA from a tumor from a patient with glioblastoma, an aggressive type of cancer. The RNA was then replicated to make a vaccine from mRNA, which is a blueprint for what is inside every cell, including tumor cells.

"These results represent an exciting advance in next generation cancer therapies that leverage mRNA, the same class of medicines used in the COVID-19 vaccines," Owen Fenton, an assistant professor of pharmacoengineering and molecular pharmaceutics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Moving at the speed of cancer

People have been developing cancer vaccines, or treatments that boost the body’s immune system attack against cancer cells, since the 1800s. However, cancer vaccines rarely mount an immune response strong enough to overcome the cancer.

Cancers mutate rapidly, so if doctors cut out a tumor and do a biopsy, the tumor itself may be different within 24 hours, said study senior author Dr. Elias Sayour, a pediatric oncologist and associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of Florida.

And by the time immune therapy begins, “the cancer is out of control now and so now the immune response is like a water gun in the face of a forest fire," Sayour told Live Science.

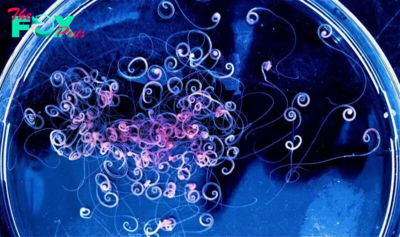

Up until now, cancer vaccines being tested have aimed to mount an immune response to a small number of molecular signatures from tumors from many different patients. In clinical trials, the vaccine material is often packaged into tiny lipid nanoparticles, but the trials typically only deliver a small number of particles and the vaccines themselves take months, if not years, to develop. However, cancer cells can adapt very quickly, figuring out ways to disable or block recognition by the local immune system.

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoTeens Are Stuck on Their Screens. Here’s How to Protect Them

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Pulmonary Rehab Can Help Improve Asthma Symptoms

-

Health1d ago

Health1d ago10 Things to Say When Someone Asks Why You’re Still Single

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoHow Colorado is trying to make the High Line Canal a place for everyone — not just the wealthy

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots