Health

DNA from dozens of human skeletons unravels history of malaria

Ancient DNA recovered from human skeletons has begun to reveal the history of how malaria spread around the globe, including how the disease first reached the Americas.

The history of humankind is outlined in stories, songs and artifacts created over tens of thousands of years. However, fewer traces remain of the pathogenic passengers that have accompanied us on this journey. Malaria is particularly mysterious because the parasitic infection causes symptoms common to a wide range of illnesses — and, when it kills, it leaves no physical marks on human bones for archaeologists to find.

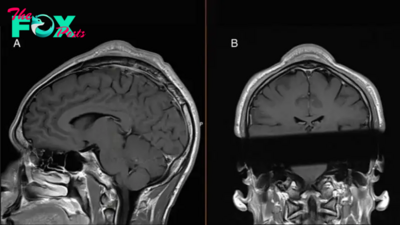

Over the past decade, though, advances in ancient DNA sampling have enabled scientists to retrieve pathogen DNA from human skeletons many thousands of years old. Traces of the pathogens that invaded a person's blood — including the parasites behind malaria — remain embedded in their bones and teeth after death, for example.

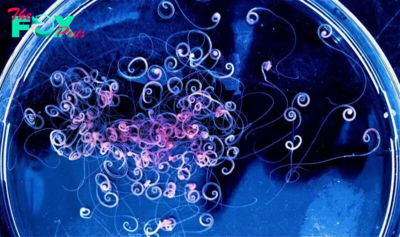

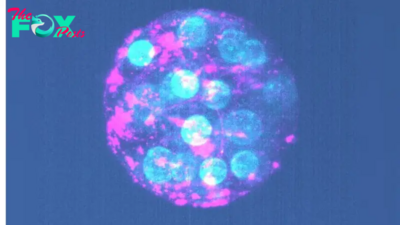

Now, these techniques have enabled researchers to investigate the epidemiology of two malaria-causing parasites: Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax.

Related: Children can be stealth superspreaders of malaria to mosquitoes

To learn how these parasites spread around the world, researchers examined DNA from the remains of 36 people whose ages span 5,500 years and who hailed from five continents. They described their results in a study published Wednesday (June 12) in the journal Nature. By comparing the genomes of the Plasmodium parasites that infected these individuals, the researchers traced when and how malaria traveled from one region to another.

"From an evolutionary biology perspective, malaria is one of the most interesting pathogens to look at because of the profound impact it has had on the human genome," said lead author Megan Michel, a doctoral candidate at Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. There are versions, or variants of genes involved in forming red blood cells — where malaria parasites multiply — that can offer resistance to the disease; these variants are more common among people whose ancestors lived in areas with high rates of malaria.

-

Health18h ago

Health18h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health19h ago

Health19h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Colorado is trying to make the High Line Canal a place for everyone — not just the wealthy

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoColorado’s pioneering psychedelic program gets final tweaks as state plans to launch next year

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight