Health

Colorado now has the worst outbreak of bird flu among dairy cattle in the country

Colorado’s outbreak of bird flu among dairy cattle is now the worst in the country, with more cases in the past month than any other state, according to the latest state and federal data.

As of Monday evening, Colorado had identified 26 herds with cases of avian influenza. Of those, 22 were identified within the past month and the herds are still in quarantine. Four other cases were identified earlier and quarantines have since been lifted.

All affected herds are in the northeastern part of the state.

The rapid and still largely mysterious spread in Colorado — hardly a leading dairy state — contributes to growing concerns that U.S. health authorities are not doing enough to contain the virus. While the threat currently to humans is generally very low, infectious disease experts worry that the longer the virus spreads unchecked through animals, the greater the chances become that it will mutate to become more dangerous to people.

Dr. Maggie Baldwin, the state veterinarian, said Colorado agriculture and Health officials are working closely with dairies to identify cases of the virus and to try to prevent its spread.

“This is just a virus that likes to hang around,” she said. “It’s really hard to mitigate once it’s in a sustained population. … I think if we all implement really strong biosecurity we absolutely can prevent the spread, but it’s in a really close geographic region.”

☀️ READ MORE

Kansas forced Colorado to stop irrigating 25,000 acres of farmland. Was it too soon to put them in the same room?

It’s a pup! Colorado wildlife officials confirm Grand County wolves have reproduced.

A Mesa County program meets people — and their produce needs — where they are

Colorado’s nation-leading numbers

Colorado’s recent cases far exceed those in any other state — Iowa and Idaho are the only other states to record double-digit case totals in the past month, with 12 and 10, respectively.

Colorado’s case total since bird flu was first identified in dairy cattle this spring places the state second nationally, behind only Idaho and one ahead of Michigan. But Colorado ranks far lower in dairy production than those states — the state was 13th in the country for milk production in 2023, according to federal data.

There are slightly more than 100 dairy herds in Colorado, meaning the bird flu outbreak has now hit one-quarter of all herds in the state. On a per-cow basis, Colorado’s outbreak is roughly three times worse than Idaho’s, which has approximately 667,000 dairy cattle compared with 201,000 in Colorado.

Baldwin suggested that Colorado’s efforts at disease detection may be reflected in the state’s high numbers. She said the state has put in a lot of work getting information to dairy producers, as well as industry associations and veterinarians.

“We’re trying to really encourage early diagnostics, early reporting and really good symptom monitoring,” she said, “and I think the relationships that we’ve established in the state have allowed for producers to feel like they can come to us when they have a problem.”

Baldwin said most cattle that are infected with bird flu are recovering from the disease — though she doesn’t have exact numbers, she has not heard reports of unusual mortality rates. But farmers are suffering from lost production during infection periods, and she said some cattle may not return to full milk production.

“The more that we’re seeing our producers be affected by this, I think the more seriously they’re taking it and saying, ‘We really want to do what we can to stop this and to be good neighbors,’” Baldwin said.

How bird flu is spreading

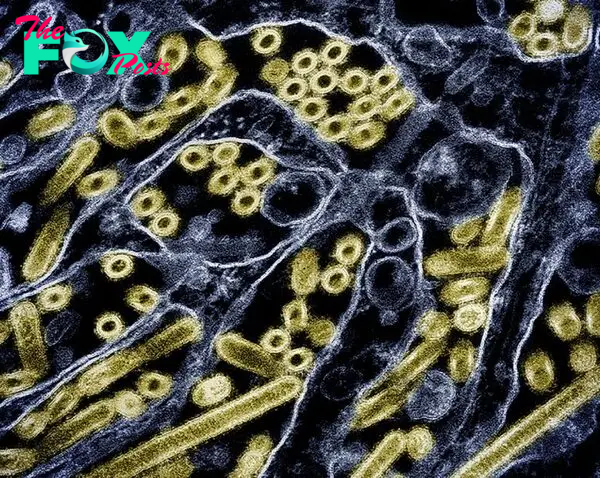

Bird flu, as the name suggests, is not something that usually infects cattle, and the initial “spillover” infections were believed to have been caused by wild birds hanging around dairy farms in the Texas panhandle.

Its subsequent spread to dozens of herds in at least 12 states was initially blamed on the movement of cows from farm to farm. Federal agriculture officials clamped down on this movement by requiring animals moving across state lines to be tested.

But, as the outbreak has persisted, a more complicated picture of spread has emerged.

Baldwin said some of the affected cattle in Colorado are in what are known as “closed herds” — meaning there is no movement of cattle in and out, making it impossible for the virus to have spread to that herd through the introduction of an infected cow. U.S. agriculture officials found something similar with several herds in Michigan.

Focus has now turned to the potential for what is called fomite transmission, in which the virus hitches a ride on an inanimate object. In this case, workers or veterinarians moving between herds could inadvertently be carrying the virus on their clothing or on equipment as they travel from farm to farm.

Baldwin said the state is working with dairy operators on detailed biosecurity plans for their dairies. This includes lots of personal protective equipment — not just masks, goggles and face shields for workers, but also booties and coveralls that can be thrown away before leaving a farm. It also includes plans for cleaning vehicle tires or other pieces of equipment leaving the dairy.

-

Health11h ago

Health11h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health12h ago

Health12h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts