Health

'We don't yet have the know-how to properly maintain a corpse brain': Why cryonics is a non-starter in our quest for immortality

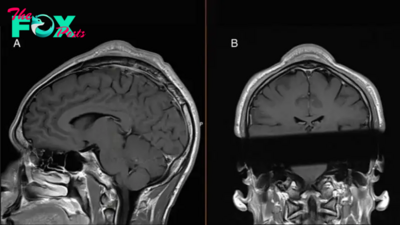

It's a scene plucked from Science fiction: On their deathbed, a person is completely frozen and then stashed away, so that they might be revived in the future. But could it be possible? In this excerpt from "Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality," (Harper Collins, 2024) Nobel Prize-winning biologist Venki Ramakrishnan examines the decades-long quest for cryonic preservation — in which people would be frozen at the point of death and defrosted in the future — and the pitfalls of an industry borne out of the idea.

Egyptians mummified their pharaohs so that they could arise corporeally at some point in the future for their journey in the afterworld. Surely now, a few millennia after the pharaohs and with more than a century of modern biology behind us, we would not do anything even remotely so superstitious. But in fact, there is a modern equivalent.

Biologists have long wanted to be able to freeze specimens so that they can store and use them later. This is not so straightforward because all living things are composed mostly of water. When this water freezes into ice and expands, it has the nasty habit of bursting open cells and tissues. This is partly why if you freeze fresh strawberries and thaw them, you wind up with goopy, unappetizing mush.

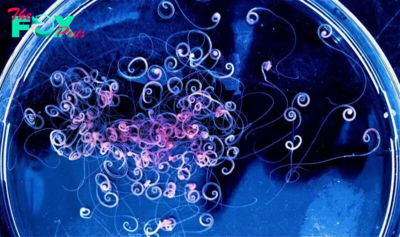

An entire field of biology, cryopreservation, studies how to freeze samples so that they are still viable when thawed later. It has developed useful techniques, such as how to store stem cells and other important samples in liquid nitrogen. It has figured out how to safely freeze semen from sperm donors and human embryos for in vitro fertilization treatment down the road.

Animal embryos are routinely frozen to preserve specific strains, and biologists' favorite worms can be frozen as larvae and revived. For many types of cells and tissues, cryopreservation works. It is often done by using additives such as glycerol, which allow cooling to very low temperatures without letting the water turn into ice — effectively like adding an antifreeze to the sample. In this case, the water forms a glass-like state rather than ice, and the process should be called vitrification rather than freezing (the word vitreous derives from the Latin root for glass), but even scientists casually refer to it as freezing and the specimens as frozen.

Enter cryonics, in which entire people are frozen immediately after death with the idea of defrosting them later when a cure for whatever ailed them has been found. The idea has been around a long time, but it gained traction through the work of Robert Ettinger, a college physics and math teacher from Michigan who also wrote Science fiction. Ettinger had a vision of future scientists reviving these frozen bodies and not only curing whatever had ailed them but also making them young again.

In 1976 he founded the Cryonics Institute near Detroit and persuaded more than 100 people to pay $28,000 each to have their bodies preserved in liquid nitrogen in large containers. One of the first people to be frozen was his own mother, Rhea, who died in 1977. His two wives are also stored there — it is not clear exactly how happy they were to be stored next to each other or their mother-in-law for years or decades to come.

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Colorado is trying to make the High Line Canal a place for everyone — not just the wealthy

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoColorado’s pioneering psychedelic program gets final tweaks as state plans to launch next year

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight