Entertainment

Southbank and the Barbican have a good time Easter with genuine Bach performances – Seen and Heard Worldwide

United Kingdom Bach: Soloists, Orchestra and Choir of the Age of Enlightenment / Peter Whelan (director and harpsichord). Queen Elizabeth Corridor, London, 27.3.2024. (CSa)

United Kingdom Bach: Soloists, Orchestra and Choir of the Age of Enlightenment / Peter Whelan (director and harpsichord). Queen Elizabeth Corridor, London, 27.3.2024. (CSa)

Bach – Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen (Rejoice you hearts), BWV 66; Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden (Stick with us for night falls), BVW 6; Oster-Oratorium (Easter Oratorio), BWV 249

Miriam Allan (soprano)

Rebecca Leggett (mezzo-soprano)

Ruairi Bowen (tenor)

Malachy Body (baritone)

Bach: Academy of Historic Music / Laurence Cummings (director, harpsichord and organ). Barbican Corridor, London, 29.3.2024.

Bach – St Matthew Ardour, BWV 244

Nicholas Mulroy (tenor) – Evangelist

George Humphreys (bass) – Christ

Anna Dennis (soprano)

Tim Mead (alto)

Mhairi Lawson (soprano)

Magid El-Bushra (alto)

Paul Hopwood (tenor)

Rodney Earl Clarke (bass)

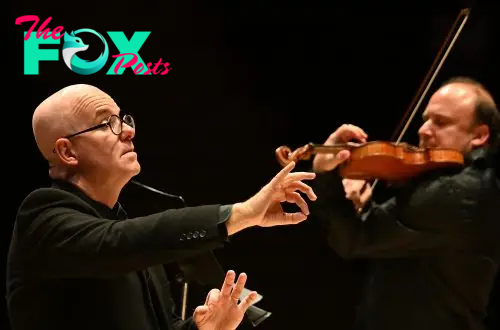

London’s musical response to Holy Week was dominated by two small-scale, traditionally knowledgeable performances of choral works by Bach. On the Southbank, Olivier Award-winning Peter Whelan directed the Orchestra and Choir of the Age of Enlightenment from the harpsichord in a programme of Easter cantatas topped by an uplifting account of the Easter Oratorio, whereas throughout the river within the Barbican Corridor, the Academy of Historic Music led by the scholarly Laurence Cummings, gave a meticulous and dedicated efficiency of St Matthew Ardour.

The wood-panelled 900-seat auditorium of the externally brutalist Southbank’s Queen Elizabeth Corridor offered a surprisingly intimate and finely balanced acoustic for Whelan’s lowered forces: some 27 gamers on interval devices and a choir of 17 from whose ranks the night’s 4 principal singers emerged after which returned. Refined lighting bathed the black-clad musicians in an old-masterly chiaroscuro glow, lending the live performance a painterly heat and authenticity.

The primary half of the night comprised a pair of cantatas written or moderately tailored by Bach particularly for Eastertide, the exuberant Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen, BWV 66, and the deeply meditative Bleib bei uns, den es will Abend werden, BWV 6. Bach recycled a few of his secular compositions into sacred music to create these two starkly contrasting works. Juxtaposed in the identical programme, they illustrated the central theme of the night: simultaneous grief and pleasure, aptly summarised within the title of Joanna Wyld’s programme notice: ‘Salty tears and laughter’, a line she plucked from the textual content of a duet from the Easter Oratorio.

Whelan drove the effusive opening refrain of BVW 66 with energy and vigour whereas the metaphorical discourse between hope (the excellent tenor Ruairi Bowen) and concern (silver-voiced mezzo Rebecca Leggett) had been buoyantly accompanied and completely executed on the violin by the OAE’s completed chief (the appropriately named Margaret Faultless). In a dramatic change of temper, Cantata BWV 6 displays on the eventide of life and inevitability of dying with contented resignation. Leggett, conveying that message to the letter, introduced sweetness and delicate grace to the primary chorale, whereas Bowen beguiled within the remaining aria with a efficiency of melancholic depth.

The all-too-infrequently carried out Easter Oratorio – the centre piece of the night – was composed in Leipzig in 1725. It tells the story – in flip exultant and sorrowful – of the primary Easter Sunday. It begins with the 2 Marys (Magdalene and mom of Simon), who on discovering Christ’s empty sepulchre, excitedly inform the disciples of His resurrection. The opening two part Sinfonia, propelled by Whelan’s insistent beat, burst forth in a stunning volley of valve-less Baroque trumpet (David Blackadder and his colleagues) and reverberant timpani (Adrian Bending). Then got here a heart-rending Adagio wherein Daniel Bates’s oboe solo sounded a pensive, plangent notice adopted by a restoratively merry ‘Kommt, eilet und laufet’ from the choir. The singing, total, was superb; by no means extra so than within the solo arias the place voices and instrumental obligatos intertwined. Dulcet-toned soprano Miriam Allan accompanied by the honeyed transverse flute of Lisa Beznosiuk wove mellifluously collectively within the stressed ‘Seele, deine Spezereien’, whereas Bowen’s crystalline voice mixed with soulful recorders (Sarah Humphrys and Catherine Latham) to offer the anguished ‘Sanfte soll mein Todeskummer’ a piercing but tender magnificence. Rebecca Leggett displayed an intrinsic understanding of the operatic ingredient in Bach’s oratorio, significantly her account of ‘Saget, saget mir geschwinde’ which injected a way of virtually breathless urgency, even desperation, to Magdalene’s seek for the lifeless Jesus. A serene and richly sung recitative ‘Wir sind erfreuet’ from baritone Malachy Body led lastly to ‘Preis und Dank bleibe’, an unabashed refrain of reward and welcome for the risen Christ, triumphant Lion of Judah.

Three days after the OAE’s live performance and all of the rejoicing related to Christ’s Resurrection, however chronologically out of flip, got here a efficiency of St Matthew Ardour, Bach’s non secular journey depicting the extraordinary human struggling of Jesus earlier than and through his Crucifixion. In an illuminating pre-concert interview on the Barbican Centre on Good Friday, Laurence Cummings, the distinguished director of the Academy of Historic Music, reminded us that the St Matthew Ardour has been described as ‘the perfect opera that Bach by no means wrote’. Acknowledging the highly effective drama of the Ardour – ‘a theatre of the thoughts which invitations the viewers into the story’ – Cummings set out his imaginative and prescient for the present manufacturing. Quoting the late Trevor Pinnock who claimed that the work must be ‘a communal act of worship’ which established a ‘convection present between listener and performer’, Cummings promised a ‘stripped-back’ model wherein two small orchestras, two organs and two four-member choirs representing ‘a continually dysfunctional group’ would have interaction with and towards one another in a state of dialogue and fixed stress. The 2 choirs comprised the eight soloists, together with the storytelling Evangelist who would sing all of the choruses as properly.

Many people grew up with expansive recordings of non secular works by Bach, and their huge choruses and opulent sonorities can nonetheless stir the soul. But these can even obscure the element of Bach’s intimate counterpoint and lack the agility and dynamic modulation of smaller scale productions. Cummings’s method, akin to that of a restorer peeling away centuries-old layers of varnish from an eighteenth-century altarpiece, succeeded in exposing the lustrous grain of the rating, and revealed a lot of its usually, unappreciated particulars.

The taking part in and singing had been dextrously supervised by Cummings, conducting from the harpsichord and organ, and was for probably the most half, very completed. Nicholas Mulroy (tenor) because the Evangelist recounted Matthew’s story with assurance, exemplary readability of diction, and nice tenderness. The purity of his higher vary gave his account of Christ’s dying on the cross an aching magnificence. Jesus was sung by bass George Humphreys. Combining calm authority and stoicism, his heat full voice gave strains like ‘Du sagest’s’ and his remaining beseeching phrases to God: ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabachtani’, an insufferable sense of resignation. Anna Dennis’s velvet soprano enchanted in legato passages, and her extraordinary breath management and vocal dexterity made innumerable lengthy runs seem easy. Beauteous Softness is the title of countertenor Tim Mead’s second CD, and he introduced mushy magnificence and spirituality to the alto elements, significantly the arias ‘Erbarme dich, mein Gott’ and ‘Sehet, Jesus hat die Hand’.

Undoubtedly, the excellence and profound dedication of the singers and Gamers made for an fascinating, clever and at instances, deeply transferring efficiency. If, nonetheless, the general goal of this manufacturing was to convey the Ardour’s immense drama, it didn’t succeed. One might attribute this to the challenges that small ensembles face when performing within the Barbican’s 2000-seat auditorium, and to the truth that there was no separate or sufficiently giant choir to emphasize within the theatrical means Bach had meant, the horrors and realities of Christ’s dying. Calls from the gang demanding crucifixion ‘Lass ihn kreuzigen’ or ‘Sein Blut komme über uns’ (Let His Blood be on us) merely lacked the requisite vehemence and chunk. It might even have been because of the truth that the singers, together with the Evangelist himself, remained static and distanced behind the Gamers, by no means transferring to the entrance of the platform to ship their recitatives, solo arias and ariosos. A considerate and thought-provoking afternoon to make sure, however one wherein the promised convection present between performer and viewers by no means materialised.

Chris Sallon

-

Entertainment15m ago

Entertainment15m agoGladiator II Belongs to Denzel

-

Entertainment16m ago

Entertainment16m agoJJ Velazquez on Finding Freedom, From Sing Sing to Sing Sing

-

Entertainment5h ago

Entertainment5h ago13 Most Romantic Movies Based on Novels

-

Entertainment5h ago

Entertainment5h agoThe Monkey Is the Secret Hero of Gladiator II

-

Entertainment5h ago

Entertainment5h agoHow Wicked Connects to The Wizard of Oz

-

Entertainment7h ago

Entertainment7h agoWhere Is Yellowstone’s Kelly Reilly From? Fans Shocked When She Reveals Real Accent

-

Entertainment7h ago

Entertainment7h agoWhy Is the ‘Wicked’ Movie Split in 2 Parts? Director Jon M. Chu Explains Reasoning

-

Entertainment10h ago

Entertainment10h agoAll About That Major Surprise Cameo in the Wicked Movie