Health

Pregnancy may speed up 'biological aging,' study suggests

Women in their early 20s who have been pregnant are "biologically older" than those who have never been pregnant, and by some measures, this age gap seems to widen in people who have had multiple pregnancies, a new study suggests.

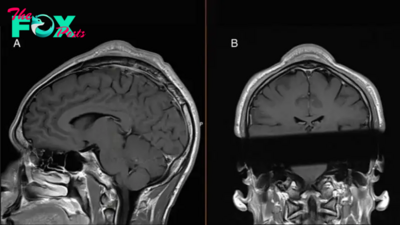

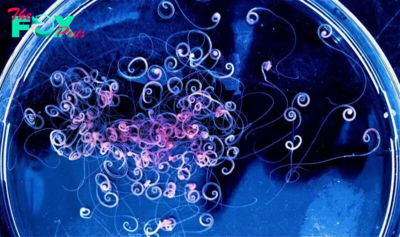

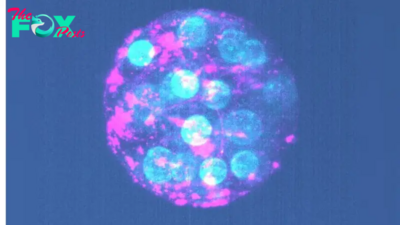

The research, conducted in the Philippines, used various tools to look at people's epigenetics, meaning the chemical tags attached to their DNA. These tags don't change the DNA's underlying code but rather help control which genes are activated and to what degree. The new study specifically looked at methyl groups, a type of molecule long linked to different aspects of the aging process.

By studying patterns of methylation seen throughout the human life span, scientists have created a number of "epigenetic clocks" that can be used to assess a person's biological age. While chronological age simply reflects how long someone's been alive, biological age reflects their physiological state and chances of age-related diseases and death.

"What epigenetic clocks are doing is they're serving a predictive function rather than a sort of causal explanation," said first study author Calen Ryan, an associate research scientist in the Columbia Aging Center. "They're trained to predict things that we think of as representing aspects of aging." So one clock may be designed to predict a person's chronological age, while others predict a person's likelihood of death and still others estimate the length of their telomeres, the protective caps at the end of DNA that keep it from fraying.

Related: 'Biological aging' speeds up in times of great stress, but it can be reversed during recovery

The research, published Monday (April 8) in the journal PNAS, used six different epigenetic clocks to make predictions about 1,735 young women and men in the Philippines. The full group had blood samples taken in 2005, between the ages of 20 and 22. A subset of the women — around 330 — who became pregnant in the years following their first blood sample also had a second sample taken about four to nine years afterward.

Across all of the clocks used, women who'd had at least one pregnancy showed accelerated aging compared with women with no pregnancy history, the analysis revealed; the pregnancies included those that resulted in miscarriages, stillbirths and live births. The pattern still showed up when the scientists controlled for other factors that also affect a person's rate of biological aging, such as socioeconomic status, smoking history and some genetic risk factors.

-

Health6h ago

Health6h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health8h ago

Health8h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health14h ago

Health14h agoHow Colorado is trying to make the High Line Canal a place for everyone — not just the wealthy

-

Health23h ago

Health23h agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoColorado’s pioneering psychedelic program gets final tweaks as state plans to launch next year

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight