Politics

Local government controls your roads, schools and utilities − but that doesn’t mean the US president doesn’t touch your life in important ways

“All Politics is local” is a common refrain – and yet, it is also true that the president has some unique powers.

I am an expert on state policymaking, and I’m teaching presidential politics at Auburn University during this election season. Researching and teaching about both state and national politics has made me keenly aware of the stakes of the different races up and down the ballot this fall.

Power close to home

State and local governments shape our daily experiences in practical ways. State governments determine whether residents have access to expanded Medicaid, reproductive care, parental and family leave, and they set the state property, sales and income taxes, which we are all required to pay.

City councils, county boards and school boards determine the quality of the roads we travel, the selection of books in school libraries and the prices of utilities such as water and sewer service.

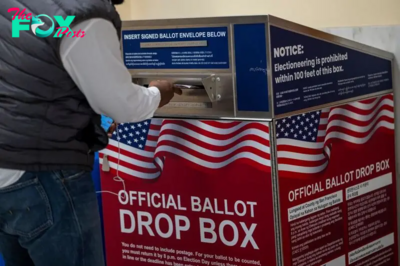

Most Americans will have the opportunity to vote for a variety of state and local elected officials this November. Yet many voters find their attention drawn to a more captivating contest: the presidential election.

And it is hard to deny that the president has an outsized influence on American public policy.

Staffing the government

So what does the president do?

It’s a busy job, for sure – including tasks such as signing executive orders, making treaties, vetoing or signing congressional bills, acting as the military’s commander in chief, attempting to build public support for their agenda and fundraising for the party.

But one other big responsibility is often overlooked – that of passing out thousands of positions in the executive and judicial branches.

The president’s appointment power is an enumerated power, meaning that it is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

As the size of the judiciary and federal bureaucracy has grown over the past century, this presidential power has ballooned to include 4,000 appointments that turn over at the start of every administration. That doesn’t even include the vacancies that arise during the president’s term – for example, when a federal judge retires or dies.

Perhaps the most well-known presidential appointment power is the power to nominate Supreme Court justices. These nominations tend to be highly political and dramatic affairs. This is due to their irregular and often sudden timing and to the high stakes of lifetime appointments.

Some presidents don’t get to exercise this supreme power as much as they would like. But they still get to fill many other judgeships across the district courts, appellate courts and other federal courts.

The Founding Fathers were adamant that the executive appointment power was not unilateral, as evidenced in Federalist Paper 76 penned by Alexander Hamilton. For 1,200 of the most consequential positions, the president nominates individuals, who are then confirmed – or not – by the U.S. Senate.

The Founding Fathers perceived this as important for preventing the tyranny of a sole actor, which they had just worked so hard to leave behind under English rule.

Assembling a Cabinet

Some of the most consequential of these appointments are members of the presidential Cabinet.

Much like how a head football coach assembles a team of assistants to enact their vision, the president convenes a team of policy champions to lead the 15 executive departments in the federal bureaucracy.

Each department is run by a “secretary,” nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The president consults with Cabinet members at periodic meetings, but secretaries otherwise enjoy a great deal of autonomy. For this reason, the president tries to pick Cabinet members who share their policy perspective.

Much of the agenda presidents claim credit for is, in fact, achieved by the Cabinet departments. For example, during the current Biden administration, the Department of Labor increased guaranteed overtime compensation, the Department of Health and Human Services recommended making marijuana a legal but regulated drug, and the Department of Education launched an initiative to tackle the post-COVID surge in chronic absenteeism.

Cabinet members often fly under the radar of the media, and consequently voters, with a few exceptions. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg had his moment in the headlines earlier in 2024 when he announced a new federal rule that entitles airline passengers to prompt cash refunds when their flights are canceled or delayed. President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Education Arne Duncan was well known for his bus tours promoting the economic value of education. President George W. Bush’s Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spearheaded the noteworthy 2008 U.S.-India nuclear agreement.

Crisis manager in chief, ad hoc

Presidents also have the power to touch voters’ lives in profound ways by serving as a unifying character during national crises, a role that differentiates the president from other elected officials.

These crises, unforeseen at the time of the election, require the president to swiftly reassure a distressed nation. For example, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush delivered an address that acknowledged the grief of Americans while imparting a stern guarantee that the United States would not cower to terrorists. President Donald Trump provided direction for a national response to an unprecedented global pandemic. President Bill Clinton shared heartfelt remarks at the memorial service of those killed in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. And Obama honored victims of a racially motivated shooting at a church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Presidential candidates of course cannot campaign on their ability to handle unpredictable, emergent situations. Instead, they talk up personal traits that will equip them to carry the nation through the next four years – whatever that may bring.

During the recent 2024 presidential debate between Democratic candidate Kamala Harris and Republican candidate Donald Trump, the candidates tried to demonstrate traits such as strength, humor and mental sharpness – all of which would prove invaluable during whatever the next four years throws our way.

This November, voters will consider a diverse spread of candidates, from city mayor to president, each with important responsibilities.

National, state and local governments work together to shape our perceptions, good or bad, about the role public policy plays in our lives – and I’d encourage voters to pay attention to candidates at both the top of the ballot and further down.

-

Politics1h ago

Politics1h agoWhat Happens if a Candidate Contests the Results of the 2024 Election?

-

Politics1h ago

Politics1h agoSupreme Court Will Weigh in on New Mostly Black Louisiana Congressional District After Election

-

Politics3h ago

Politics3h agoTavis Smiley: Black American Men Must Hold Candidates Accountable

-

Politics8h ago

Politics8h agoWhy the Election Could Come Down to Black Men in a Few States

-

Politics8h ago

Politics8h agoHarris Pitches Positive Closing Message in Michigan

-

Politics13h ago

Politics13h agoWhat a Kamala Harris Win Would Mean for Immigration

-

Politics13h ago

Politics13h agoHow to Check if Your 2024 Presidential Election Ballot Has Been Counted

-

Politics19h ago

Politics19h agoWho Will Replace Mitch McConnell as Senate GOP Leader? It Remains Deeply Uncertain