Science

Experts predicted way more hurricanes this year — here's the weird reason we're 'missing' storms

Back in April and May 2024, various universities and weather agencies predicted there would be more hurricanes in the Atlantic than usual this year. Warm seas meant conditions were perfect for a particularly active season, they said, with somewhere between 15 and 25 named storms.

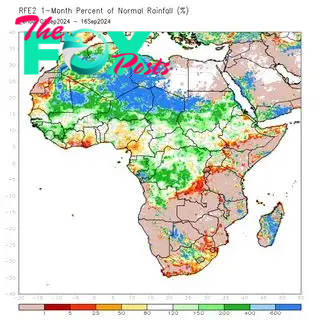

Yet by mid-September, the typical peak of the hurricane season, only seven storms have been named. Where are the "missing" hurricanes in the Caribbean? To understand what happened, and why the models seemingly got it so wrong, we can't look at the Atlantic in isolation. The key difference this year was unprecedented rain in an unexpected place: the Sahara desert.

The 2024 hurricane season kicked off with a bang: Hurricane Beryl, which made landfall on the island of Carriacou in Grenada on July 1, was the earliest category 5 storm on record. After Beryl, there was a quiet period: an outbreak of Saharan dust meant that the air over the tropical Atlantic was too dry to sustain the moist clouds needed to develop a hurricane. July is generally a less active part of the season, so this is not too unusual: only one storm was named in July between 2021 and 2023.

In early August, Beryl was followed by Hurricanes Debby and Ernesto, but between August 13 and September 3, there were no named storms in the Atlantic at all. That's only happened once before on those dates, back in 1968.

In 2023, the hottest seas on record led to 20 named storms in the Atlantic, the fourth most active hurricane season on record. This year, the sea is just as hot, as predicted by the climate models. However, other factors that inhibited hurricane development were not anticipated as reliably.

From 'waves' in Africa, to Caribbean hurricanes

Between June and September, west Africa typically experiences a monsoon: wet air from the Gulf of Guinea Travels northward, bringing rain and thunderstorms to the transitional region between the rainforests of central Africa and the Sahara — an area known as the Sahel. This creates a stark contrast in land temperatures between the wet, green Sahel, and the dry desert to its north, which in turn allows a high-altitude "atmospheric jet" to form.

Smaller "waves" can spin off from this jet. We call them African easterly waves, since they originate in the east and move westward over Africa, and these are linked to large thunderstorms and low pressures. Strong easterly waves can move off the coast of Africa and create areas of low pressure and rotating air in the Atlantic, which can become hurricanes. It is estimated that around 60% of major Atlantic storms can be traced back to these waves.

-

Science2d ago

Science2d agoInside Capitol Hill’s Latest UFO Hearings

-

Science2d ago

Science2d agoYou Won’t Want to Miss the Leonid Meteor Shower. Here’s How and When You Can See It

-

Science3d ago

Science3d agoHere’s What Trump’s Win Means for NASA

-

Science6d ago

Science6d agoWhy Risky Wildfire Zones Have Been Increasing Around the World

-

Science6d ago

Science6d agoIt’s Time to Redefine What a Megafire Is in the Climate Change Era

-

Science1w ago

Science1w ago4 Astronauts Return to Earth After Being Delayed by Boeing’s Capsule Trouble and Hurricane Milton

-

Science1w ago

Science1w agoThe Elegance and Awkwardness of NASA’s New Moon Suit, Designed by Axiom and Prada

-

Science1w ago

Science1w agoSpaceX Launches Its Mega Starship Rocket. This Time, Mechanical Arms Catch It at Landing