Health

Ballot Issue 2Q: A Denver sales tax increase that could provide a lifeline for Denver Health

Denver voters this year will decide whether to toss a financial lifeline to the city’s safety net hospital and health system, Denver Health.

The system serves a disproportionately low-income population both in its hospital and through a network of community and school-based clinics. But it has been struggling with higher amounts of what is known as uncompensated care — care that a hospital provides but does not receive payment for. That has placed the hospital in a more precarious financial position.

>> Colorado’s 2024 election guide

Ballot Issue 2Q, which appears only on the ballots of voters in Denver, would raise the city’s sales tax rate by 0.34% — 3.4 cents on a $10 purchase — to provide funding for Denver Health. It is estimated to raise $70 million a year to start.

Here’s what else you need to know about Ballot Issue 2Q.

Why does Denver Health need the money?

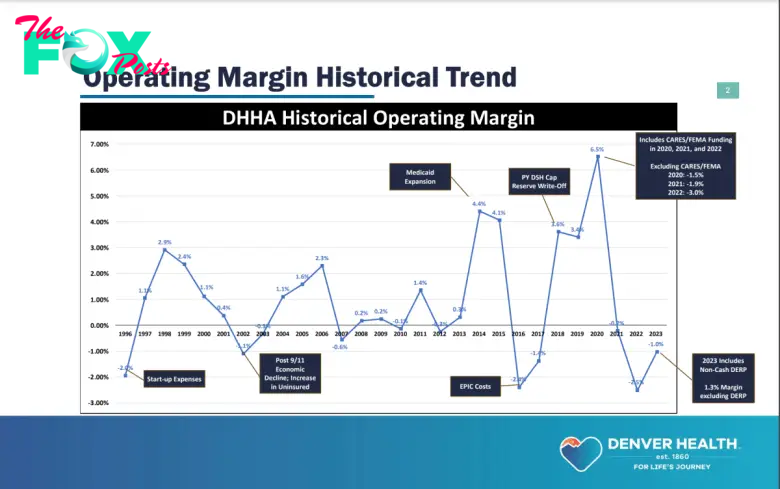

For decades, the annual balance sheets for Denver Health have looked like a child’s drawing of the Rocky Mountains.

Up, down, up, down through jagged peaks and steep valleys.

“Our finances over multiple years have been a little like a roller coaster, one year is OK, another year’s bad,” Denver Health CEO Donna Lynne said.

But then came the COVID-19 pandemic. Emergency funding in 2020 pushed the hospital’s profit margin from operations to record heights. But in 2022, inflation, higher staffing costs and fundamental shifts in the insurance market smushed Denver Health’s margins into the deepest hole in over two decades.

The hospital lost around $32 million on operations in 2022. It turned a roughly $9 million profit in 2023, but one-time boosts from the state legislature and Kaiser Permanente contributed to that. This year, Denver Health expects to lose about $8.5 million, and as of June, the hospital had just a little over two months’ worth of cash-on-hand. (Best-practice standards usually call for around six months or more.)

☀️ READ MORE

Colorado’s 2024 ballot is very crowded. Will voters fill out every bubble?

Would Amendment 79 allow Colorado taxpayer funds to be used to pay for abortions?

Ballot Issue 2R: A Denver sales tax hike could generate $100M a year for affordable housing

If passed, Ballot Issue 2Q would help Denver Health build up a cushion. But it still wouldn’t be enough to wipe out one of the hospital’s biggest reasons for struggling — the amount of care it provides but doesn’t get paid for as a safety net hospital.

Also known as uncompensated care, the figure is estimated to hit $155 million for 2024, Lynne said, compared with $60 million in 2020.

Why is uncompensated care increasing?

About half of what Denver Health counts as uncompensated care is tied to Medicare and Medicaid patients — both programs pay less than what it costs Denver Health to provide care, so the hospital includes the shortfall in its total for uncompensated care.

More than two-thirds of Denver Health’s patients are covered by Medicare or Medicaid. In talking about how this impacts the hospital’s finances, Lynne specifically mentioned Medicaid payment rates, which she said are increasing by only 2% next year.

“That’s not consistent with inflation; it’s certainly not consistent with medical inflation,” Lynne said. “And it’s not what we can pay our employees in terms of their salary because other systems are able to pay much more.”

The other half of Denver Health’s uncompensated care is tied to uninsured patients.

Lynne said the hospital has been seeing more uninsured patients since the state began doing eligibility renewals for members. During the pandemic, federal rules prohibited state Medicaid programs from disenrolling anyone, leading to huge numbers of people on Colorado’s Medicaid rolls. But that changed when the federal COVID-19 public health emergency expired and states again began doing annual checks to see if Medicaid members still qualified to be enrolled.

The process — known as “the unwind” — has led to hundreds of thousands of people in Colorado dropping from Medicaid coverage. Many of those may have been eligible to transition to health insurance offered through their work, or they may have been able to buy coverage on their own. But a certain, as-yet-unknown number likely remained uninsured, leading to higher rates of uninsured patients at Denver Health and other safety net medical and mental health care providers.

Lynne said the elimination of the tax penalty for not having insurance under the Affordable Care Act may have some role in the rising number of uninsured people. Broad changes in the economy — more gig workers, for example, or more people working at jobs that either don’t offer insurance or do but the insurance is unaffordable — may also contribute to the issue.

“The wages are so low, or the workers are working part-time, that being able to buy health insurance from their employer or in the private market is just untenable,” she said.

-

Health17h ago

Health17h agoThe Biggest Moments From the TIME100 Health Leadership Forum

-

Health22h ago

Health22h agoHealth Industry Experts Talk Increasing Trust and Lowering Costs

-

Health22h ago

Health22h agoHow Health Care Can Be Made More Equitable

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Women’s Health Is Global Health

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Emerging Technologies Can Transform Health Care

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoMcDonald’s Quarter Pounder Linked to Severe E. Coli Outbreak in U.S.

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoThe Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoWeight-Loss Drugs May Help Alcohol and Opioid Addiction