Archaeology

Where is Stonehenge, who built the prehistoric monument, and how?

Stonehenge is a massive stone monument located on Salisbury Plain in southern England. It was built roughly 4,000 to 5,000 years ago and was part of a larger sacred landscape.

The bigger stones at Stonehenge, known as sarsens, weigh 25 tons (22.6 metric tons) on average and are widely believed to have been brought from Marlborough Downs, 20 miles (32 kilometers) to the north, according to English Heritage, an organization that oversees Stonehenge.

Most of the monument's smaller stones, referred to as "bluestones" (as they have a bluish tinge when wet or freshly broken), come from quarries in the Preseli Hills in west Wales, about 140 miles (225 km) away from Stonehenge, a U.K. research team found in a 2015 study in the journal Antiquity. These bluestones weigh between 2 and 5 tons (1.8 and 4.5 metric tons) each, according to English Heritage. Scientists are still unsure exactly how prehistoric people moved the stones over such long distances.

One bluestone, known as the "Altar Stone," is much larger and heavier than the others (6.6 tons or 6 metric tons) and may have come all the way from northern Britain, according to research published in 2023 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Previously thought to have been brought to Salisbury Plain from the Preseli Hills around the same time as the other bluestones, the Altar Stone may challenge long-held ideas about Stonehenge.

Sacred landscape

Stonehenge is just one part of a larger sacred landscape that contained many other stone and wooden structures, as well as burials.

Before the monument was erected, the area was a hunting oasis during the Mesolithic (which in Britain ran between 11,600 to 6,000 years ago), according to a 2022 study in the journal PLOS One.

The area also holds more than 3,000 pits near Stonehenge, the oldest of which dates back more than 10,000 years. Some of the pits were used for hunting while others may have been part of ceremonial structures.

As early as 10,000 years ago, three large pine posts were erected at the site Stonehenge now sits on, likely for ceremonial purposes, wrote Mike Parker Pearson, a professor of British prehistory at University College London, in his book "Stonehenge: Making Sense of a Prehistoric Mystery" (Council for British Archaeology, 2015). "Hunter-gatherers are not generally known for building spectacular monuments, so these are something of a mystery," Pearson wrote.

Many other prehistoric structures of importance have been discovered at or near Stonehenge, including burials and burial mounds, as well as shrines — some in the shape of a circle — and a "House of the Dead" containing dozens of skeletons that date to between 3700 B.C. and 3500 B.C.

Around 3500 B.C. two rectangular earthworks now called "cursus" monuments were also built to the north of where Stonehenge would be erected, English Heritage notes.

Building Stonehenge

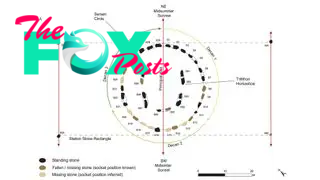

Stonehenge was built in several stages. In about 3000 B.C., a circular ditch was constructed around what would be Stonehenge along with a series of 56 holes — sometimes called "Aubrey holes" after their 18th-century discoverer John Aubrey. These holes may have held timber posts or bluestones, according to English Heritage. It's possible that the heel stone — a sarsen stone located outside the entrance to Stonehenge — was placed around this time, but this is also uncertain.

It's unknown how people at the time moved the bluestones to Stonehenge. Experiments conducted at University College London in 2016 showed that a 1-ton (0.9 metric ton) stone could be moved by 10 people on a wooden trackway, but whether this technique was actually used by the prehistoric builders is uncertain. It's possible that pig lard was used to grease any sleds that moved the stones.

In 2021, a team of archaeologists proposed in the journal Antiquity that at least some of the bluestones were arranged in a stone circle in the Preseli Hills before they were moved to Stonehenge. This suggests that the bluestones already had symbolic significance before they were moved, the team wrote.

Around 2500 B.C., people erected a series of sarsen stones on the site in the shape of a horseshoe, with every pair of these huge stones having a stone lintel connecting them. A ring of sarsens surrounded the horseshoe, their tops connecting to each other, giving the appearance of a giant, interconnected stone circle around the horseshoe. The "altar stone" — a large slab of greenish red sandstone that was brought from Wales, according to English Heritage — was placed in the middle of the horseshoe. What exactly the altar stone was used for is uncertain.

Two circles of bluestones were placed between the circle of sarsens and the sarsens in the shape of a horseshoe. Also, people erected four "station stones," as they are now called, outside Stonehenge. Around 2300 B.C., Stonehenge underwent another change as the bluestones were rearranged. One circle of bluestones was placed between the outer circle of sarsens and the sarsens in the shape of a horseshoe, and another circle of bluestones was placed within the horseshoe. Around this time, an "avenue" was built connecting Stonehenge with the River Avon, according to English Heritage.

This would be the last major construction phase that took place at Stonehenge. As time went on, the monument fell into neglect and disuse; some of its stones fell over while others were taken away.

Stonehenge was likely positioned to align with existing structures in the area. For example, it has an interesting connection with the Cursus monuments. Archaeologists found that the longest Cursus monument had two pits, one on the east and one on the west. These pits aligned with Stonehenge's heel stone and a processional avenue.

"Suddenly, you've got a link between [the long Cursus pit] and Stonehenge through two massive pits, which appear to be aligned on the sunrise and sunset on the mid-summer solstice," University of Bradford archaeologist Vincent Gaffney, who is leading a project to map Stonehenge and its environs, told Live Science in 2014.

Who built Stonehenge?

Researchers have unearthed a number of clues about the people who built the monument. Some of these people may have lived near the monument in a series of houses excavated at Durrington Walls, a nearby Neolithic settlement and that later sported a henge. According to food remains found at the site, the people who lived at Durrington Walls feasted on meat and dairy products, a 2015 study in the journal Antiquity found. The rich diet of the people who may have built Stonehenge provides evidence that they were likely not slaves or coerced, the team wrote.

It's not clear which group or states the people who built Stonehenge were affiliated with. It was built long before writing was used in Britain, making it hard to determine exactly how the island was politically organized at the time.

Many people today associate Stonehenge with the druids — mysterious pagan religious leaders in ancient Britain. However, the druids probably did not build Stonehenge. The site was constructed roughly 4000 to 5,000 years ago, while the earliest records mentioning druids date back about 2,400 years.

Additionally, the surviving records do not indicate that the druids had an interest in stone circles, much less Stonehenge, Live Science previously reported.

Despite this evidence, modern-day druids often associate with Stonehenge, flocking to the site on the summer solstice. However, the ancient druids died out around 1,200 years ago and were not revived until about 300 years ago.

Why was Stonehenge constructed?

Stonehenge is probably the most famous prehistoric monument in the world. Despite its fame, the structure is still mysterious, with its prehistoric concentric rings garnering plenty of speculation as to why and how they were constructed. Many ideas have been put forward to try and explain why Stonehenge was constructed.

One theory posits that Stonehenge marks the "unification of Britain," a point when people across the island worked together and used a similar style of houses, pottery and other items.

It would explain why people at the time were able to bring stones from other regions of Britain and how they could marshal enough labor and resources for the construction. "Stonehenge itself was a massive undertaking, requiring the labor of thousands to move stones from as far away as west Wales, shaping them and erecting them. Just the work itself, requiring everyone literally to pull together, would have been an act of unification," Pearson said in the 2012 statement.

Archaeological finds found at other sites support the idea that people in Britain were sharing artistic ideas at the time Stonehenge was built, including bone pins and sculptures with enigmatic motifs that have been unearthed at several sites.

Another theory is that Stonehenge may have been used as a solar calendar, with the stones laid out to represent 365.25 days in a year. This was proposed by Timothy Darvill, a professor of archaeology at Bournemouth University in the U.K, in a 2022 article published in the journal Antiquity.

Human burials have been found within and near Stonehenge, raising the possibility that Stonehenge may have been used as a burial ground, although most scholars think that it had a broader purpose than that. Another possibility is that it was a place of pilgrimage, where different groups could gather to perform ceremonies. It's also possible that it was used for a mix of different reasons that may have changed over time.

Ultimately Stonehenge's purpose remains a tantalizing mystery.

Additional resources

Stonehenge is overseen by English Heritage and information on visiting the site can be accessed on its website. English Heritage also offers a virtual tour of the monument. Stonehenge and the surrounding area are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and information on its designation can be viewed on UNESCO's website.

-

Archaeology15h ago

Archaeology15h agoUnveiling Priceless Treasures: The Most Unforgettable Moments Around the World.hanh

-

Archaeology3d ago

Archaeology3d agoExploring Hidden Treasures: Embark on an Electrifying Journey to Uncover Secret Riches! (Video).hanh

-

Archaeology4d ago

Archaeology4d agoHumans reached Argentina by 20,000 years ago — and they may have survived by eating giant armadillos, study suggests

-

Archaeology5d ago

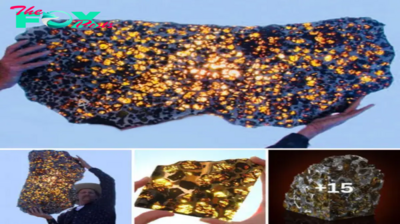

Archaeology5d agoUnveiling the $2 Million Marvel: The Enigmatic Beauty of the 925-Pound Fukang Meteorite.hanh

-

Archaeology5d ago

Archaeology5d agoEmbark on an Epic Adventure: Discover a Paradise Brimming with Hidden Treasures and Ancient Secrets!.hanh

-

Archaeology5d ago

Archaeology5d agoVenus of Brassempouy: The 23,000-year-old ivory carving found in the Pope's Grotto

-

Archaeology6d ago

Archaeology6d agoHistorical Riches Unveiled: Gold, Diamonds, and Ancient Coins Trace Back to Emperor Constantine.hanh

-

Archaeology1w ago

Archaeology1w agoStunning Tang dynasty mural in tomb unearthed in China may portray a 'Westerner' man with blond hair