Health

U.S. 50 bridge closure an “immediate 911 deal” for Gunnison Valley Hospital

As chief of the Gunnison Valley Hospital paramedics, C. J. Malcolm deals with emergencies daily. But when his phone pinged with an alert that U.S. 50 west of Gunnison was being shut down immediately due to a cracking bridge, Malcolm had an instant of heart-stopping alarm.

“I knew it was a huge, immediate 911 deal,” said Malcolm. “My first thought was, ‘this is a disaster.’”

He wasn’t overreacting.

Closing down one of two highway accesses to an isolated town of 7,000 in a county of 4,000 rugged miles posed all kinds of potential life-threatening problems.

The closure on April 18 cut off regular ambulance tranSports to larger towns to the west as well as threatening the overall operation of a small, county-owned hospital that provides everything from deliveries to orthopedic surgeries and handles an average of 20 emergency room visits in a day.

Gunnison Valley Health Hospital functions independently. Its mission as a Level IV critical care hospital is to stabilize patients in Colorado’s largest county — a county that is accident-prone due to a surfeit of remote and mountainous public lands, and residents and visitors who like to challenge themselves in that terrain.

But the hospital doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It has many tentacles of reliance on other hospitals and Health care providers and suppliers outside the Gunnison Valley. Many of those tentacles reach to the west, beyond the impassible bridge.

Just how many was quickly evident to a critical incident command team led by Malcolm and assembled with the help of the hospital’s CEO Jason Amrich. They essentially set up a dual operating structure within the hospital. One system would deal with the bridge-related problems while the hospital’s usual chain-of-command organization would keep the everyday operations running smoothly.

“You can’t address an emergency situation from a normal business approach,” Malcolm explained.

Basement room converted to a command center

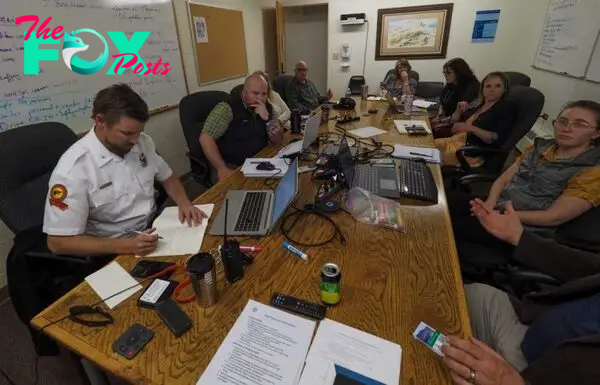

By the morning after the largest bridge over Blue Mesa Reservoir was shut down with no opening in sight, the hospital’s new critical incident system was up and running. A room in the basement of the 24-bed hospital became an official command center. Teams had formed for operations, logistics, finances and planning.

Whiteboards listing priorities and objectives bristled with colorful sticky notes. A large screen on one wall beamed in those who had to attend the twice-a-day — or more — emergency meetings virtually.

Gunnison Valley Chief Nursing Officer Nicole Huff is one of those who has been trekking to the basement several times a day for command-center meetings that she calls “brain dumps.”

“Lots of out-of-the-box thinking goes on there,” she said.

Problems quickly crowded the whiteboards: Ambulances wouldn’t be able to transport patients to hospitals in Montrose or Grand Junction for higher-level care. Such transports to outside hospitals, including some in Denver and Colorado Springs, happen around 300 times per year. Gunnison has just three ambulances, and the longer transports to the east could stretch their availability. Physicians and nurses who travel to Gunnison from the west wouldn’t be able to get to the hospital for their shifts.

Supplies of everything from linens and sample vials and filtered water to blood and oxygen and chemotherapy drugs could no longer be delivered from the normal western suppliers. Dialysis and radiation patients wouldn’t be able to get to Montrose for their daily life-sustaining treatments. Methadone patients couldn’t travel west for their normal care. The drugs for the hospital system’s senior care center would need to be rerouted from another supplier.

Solutions went up on a board next to problems: Dialyses patients could be sent east to Salida. Radiation patients could be given priority to get over a county road detour to Montrose. Chemotherapy drugs from an out-of-state supplier could be brought in by FedEx from the east rather than the west.

Blood products and oxygen could come from the east during the shutdown. Lab specimens, including biopsies, could be prioritized to get over the dirt-road detour to labs in Montrose. The county could possibly allow medical personnel to get through the rugged detour outside the allowed early morning and late evening pilot car-led openings for local citizens.

Montrose emergency services could handle ambulance cases on the east end of Gunnison County. That happened on the first day of the shutdown when a critically ill person was picked up by a care flight at the west end of Blue Mesa.

One whiteboard shows all the hospital’s important links to services to the west. Another diagrams tentacles to the east that would be able to continue with trips on U.S. 50 over Monarch Pass. Arrows showed what could be shifted directionally.

-

Health9h ago

Health9h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health10h ago

Health10h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts