Health

Neanderthals didn't truly go extinct, but were rather absorbed into the modern human population, DNA study suggests

Neanderthals may not have truly gone extinct but instead may have been absorbed into the modern human population. That's one of the implications of a new study, which finds modern human DNA may have made up 2.5% to 3.7% of the Neanderthal genome.

"This research really highlights that what we think as a separate Neanderthal lineage really was more interconnected with our ancestors," Fernando Villanea, a population geneticist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. Both modern human and Neanderthal populations "shared a long history of exchanging individuals."

Neanderthals were among the closest extinct relatives of modern humans, with our lineages diverging around 500,000 years ago. More than a decade ago, scientists revealed that Neanderthals interbred with the ancestors of modern humans who journeyed out of Africa. Today, the genomes of modern human groups outside Africa contain about 1% to 2% of Neanderthal DNA.

Related: 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

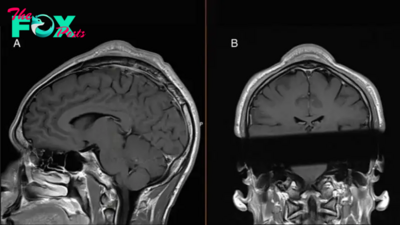

However, researchers know less about how modern human DNA may have entered the Neanderthal genome. That's largely because there are currently only three known high-quality examples of a complete Neanderthal genome that have survived — from specimens unearthed in Vindija cave in Croatia, which date to 50,000 to 65,000 years ago, and Chagyrskaya and Denisova caves in Russia, which date to about 80,000 and 50,000 years ago, respectively.

In comparison, scientists have sequenced the genomes of hundreds of thousands of modern humans since the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003.

"There has been a considerable amount of research focused on how matings between Neanderthals and modern humans affected our DNA and evolutionary history," study senior author Joshua Akey, a population geneticist at Princeton University in New Jersey, told Live Science. "However, we know much less about how these encounters impacted the genomes of Neanderthals."

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoKnee problems tend to flare up as you age – an orthopedic specialist explains available treatment options

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoThe second Trump presidency could mean big changes for health insurance in Colorado

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoIs It Time to Worry About Bird Flu?

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoJared Polis praises Trump for choosing anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as health secretary

-

Health3d ago

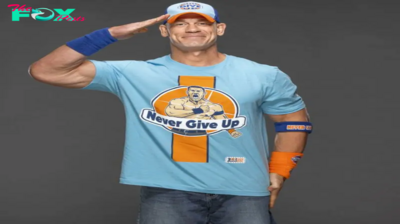

Health3d agoJohn Cena’s Workout Routine And Diet Plan: How The WWE Superstar Stays In Shape

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoSleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives