Lifestyle

Ghosts in Pakistan: 'Zinda Laash' | The Express Tribune

Horror season may have officially ended with October, but as true fans and believers will tell you: the hauntings care little for what page the calendars are turning. Much like the age-defying monsters under the bed, Zinda Laash is an atmospheric homegrown horror that prolongs the spooks long past Halloween.

Directed by Khwaja Sarfraz and produced by Habib, upon its 1967 release, the film became Pakistan's first X-rated film, noted for its impressive attention to detail in horror, with imported fangs, cliché costumes, and immersive sound design.

Aside from the horror, equally contentious was its scandalous embrace of textbook eroticism. Even though its temptations are more implied than acted upon, Zinda Laash interjected mainstream cinema with a raw sensuality not entirely misplaced given its premise. After all, few acts are more carnal than the vampire's kiss.

More than fifty years later, Habib and Sarfraz's risky (or risque) endeavour has donned the mantle of a cult classic. It is both impressive and juvenile, reminiscent of a golden uninhibited past. Despite Pakistani cinema's relative obscurity, one might expect some lone cinephile to add the film to their annual Halloween marathon. But does Zinda Laash merit a spot on such devoted lists?

Behold the great past

When Professor Tabani (Rehan) devises his Aab e Hayat (the elixir of life), he envisions immortality as its greatest promise, not its gravest peril. Lauded today as seminal horror viewing for Pakistani cinema fans, Zinda Laash begins with a curious disclaimer for a horror film.

"Every soul will taste death," Habib wisely recites the oft-quoted verse from Surah Al Imran. He then reminds the audience that life and death are solely in God's control and that no being, well or ill-intentioned, can challenge this divine authority.

The film goes on to feature three elaborate dance sequences led by women out to tempt men, women, and the cinemagoer with delirious abandon. Of these, one follows a vampire bride luring in her victim, heaving sultry sighs to an instrumental backdrop. For garden variety General Zia critics, for whom a glorious past is never empty nostalgia but always a prelude to imminent resistance, Zinda Laash is the ultimate fantasy.

How could one living in 2024's Pakistan not wonder about the possibility of such a film being made today? Amid its underlying religiosity, even more fascinating is how the film's women are neither victims nor villains. Damned to desire more, these women are surrounded by men of reason who blame their transgressions on the source of evil: man as the mad, ungodly scientist.

While didacticism has always been a hallmark of Pakistani Urdu cinema in the '60s and '70s, Zinda Laash's invocation of higher powers is both instinctive and distractingreminding us that few things stir a primal belief in the unseen like facing its horrors. Divine intervention comes as the final recourse, tapping into a long tradition of science's failure to defeat lurking demons, monsters, and spirits in fiction.

The Exorcist (1973) famously summons the Catholic church after doctors are unable to correct a demonic possession whereas Purana Mandir (1984) seeks solace in Lord Shiva to vanquish an evil magician. But Zinda Laash takes it a step further. Both its villain and hero are well-meaning men who dared to believeonly one turns to Science while the other to god.

The fate of cult

On account of being one of the few better-known Pakistani 'oldies' aside from Aina, Maula Jatt, and possibly Andaleeb and Anjuman, a serious viewer is compelled to visit Zinda Laash with reverence.

The film was released on DVD by the American-based home video label Mondo Macabro in 2003. The release featured extras, including an audio commentary by British producer Pete Tombs and filMMAker Omar Khancreator of the 2007 comedy-horror Zibahkhanaalong with a behind-the-scenes documentary and an episode of Channel 4's Mondo Macabro series, South Asian Cinema.

Tombs' interest in Zinda Laash is arguably a testament to the film's cult status. Co-founder of Mondo Macabro, his label committed to archiving obscure exploitation cinemas from all over the world in 2002. Khan, too, has generously devoted himself to establishing a local urban cult circuit with HotSpot Cafe, his B-film-themed ice cream parlour franchise.

Away from the urban gentry, Professor Tabani continues to animate Instagram pages dedicated to Pakistan's glory days, sporadically featuring the film's vintage posters and trivia. A recent upload on YouTube, which is admittedly a golden reservoir for preserving and accessing old Pakistani films, has also given Zinda Laash a little more than 3700 views.

The film definitely ticks two boxes of cult approval: dedicated following and non-mainstream appeal that gathers slowly over the years. Films like Rocky Horror Picture Show and Eraserhead have been shelved in the genre for their countercultural storytelling and execution. Others like The Room are survived by the "so bad, it's good" principle. Zinda Laash is decidedly not the latter and only begrudgingly fits the former for this Pakistani spin on vampirism is not an adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula but a marginally disloyal rendition of Hammer's Horror of Dracula (1958).

It is possible that when you feel the first inklings of admiration, they quickly fizzle out into a disappointing recognition. Sound, visuals, and narrative from Hammer's film are replicated unabashedly in many scenes. But even rip-offs can coMMAnd praise through their attention to detail. As a duo, Sarfraz and Habib excel in production design, creating an aesthetic that resonates even today.

And to their credit, there are innovations. The oft-fictionalised wooden stake is replaced by a regular knife to kill the irreverent. Count Dracula gets an origin story as a mad scientist whose experiment goes awry. The result is a glorious commentary on Science, brandished with a cartoonish romance. Rehan models his vampire after Christopher Lee's iconic Draculacomplete with slicked-back hair and a flowing black cape. His pre-transition professor wears neither a lab coat nor protective goggles. Dressed in a blazer and checkered waistcoat, he stands in a lab beside Nasreen, who Sports an extravagant updo and a mod '60s pinafore, every bit a glamorous couple heading to a soirée.

'First Pakistani horror'

Any family with a member remotely intimate with '60s cinema knows the stories that came out. Women in cinema halls shrieked and swooned. Either a lacking awareness or wilful dismissal of parental advisory exposed many children to the nightmares of Zinda Laash. As is predictably the case, all such stories ring familiar.

Rumour has it that when cinema's first gun went off in the camera's face, many audience members fainted. So what if it's universal knowledge that time wears down shock value and novelty? The Great Train Robbery's early audiences would never have imagined that there would follow generations for whom the film would be forgotten, amusing, and fascinating - and in that order.

A similar retrospective dumbing down is reserved for many Pakistani films including Zinda Laash. The blood-stained fangs, the ink-black cloaks, the seemingly futile dance inserts - all reawaken the yesteryears when film audiences were fooled and impressed by just about anything. You may watch Rehan's frontal address to the camera, a staple of Pakistani films of the '60s and '70s, and mock its theatricality. True to its melodramatic pedigree, Zinda Laash is overly chatty, its climax a culmination of avoidable misfortunes.

However, you should not return to this film expecting a novel filmscape or to chase its plot. Hammer's adaptation is the superior choice for Dracula's fate, but even at its most derivative, Zinda Laash demands to be seen and cherished simply for its existence. To be hailed as Pakistan's "first horror film" comes with its privileges, the highest of which is the forgotten fact of its plagiarism. All there is to take away is the audacity to make such a film in 1967. Even if it means being blindsided by the glory days.

-

Lifestyle10m ago

Lifestyle10m agoAishwarya Rai celebrates Aaradhya's 13th birthday, Abhishek's absence fuels speculation | The Express Tribune

-

Lifestyle4h ago

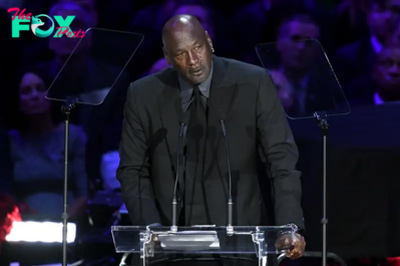

Lifestyle4h agoRevealing the Story of the Legendary Michael Jordan: At 21, He Bought 7 Supercars in One Day and Gave Away 6 for Just One Reason.Linh

-

Lifestyle4h ago

Lifestyle4h agoExplore Justin Bieber’s Lavish Lifestyle and Vast Fortune at the Age of 29.Linh

-

Lifestyle9h ago

Lifestyle9h ago“BREAKING: ABC CEO Announces Plans to Ax The View—‘It’s Just the Worst Show on TV!’”.Ngocchau

-

Lifestyle9h ago

Lifestyle9h agoBREAKING NEWS: Keenan Reeves Stands by Katt Williams and Uncovers the Dark Truth About Oprah – Shocking Revelations Exposed.Ngocchau

-

Lifestyle14h ago

Lifestyle14h agoUNHAPPY KELCE: Travis Kelce Vents Fury Over Chiefs’ First Loss, ‘It Pisses Me Off.’Cau

-

Lifestyle14h ago

Lifestyle14h agoESPN DENIES: Network Shuts Down Schefter’s Report Linking Ray Lewis to FAU Role.Cau

-

Lifestyle15h ago

Lifestyle15h agoMy Manicurist Told Me About Her Lover, Only to Realize She Was Talking About My Husband