History

Campus Protests Are Called Disruptive. So Was the Civil Rights Movement

On May 1, a half dozen U.S. Senators from both major parties read aloud Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, a yearly ritual celebrating the power of dissent in U.S. History.

Meanwhile, the night before, the NYPD had used riot gear, Military equipment, and hundreds of officers to dismantle nonviolent Gaza solidarity encampments at Columbia University and then at City College of the City University of New York (CUNY). In the process, NYPD officers, with authorization from CUNY and Columbia administrations, arrested more than 100 Columbia protesters and approximately 170 CUNY protestors.

The multiracial City College Gaza Solidarity Encampment had drawn students and faculty from across the 25 CUNY colleges, holding Passover seders, Muslim prayers, teach-ins, and art builds. Alongside their demands for divestment, disclosure, and an academic boycott of Israel, CUNY students also called for a demilitarized CUNY and free tuition. Over half of CUNY students come from households that earn $30,000 or less; the university student body is 22% Asian, 26% Black, 31% Latinx, and 21% white.

The juxtaposition of the Senate pageant with the mass criminalization of student protesters was not simply ironic. It reflects how public officials have repeatedly tried to drape themselves in the mis-History of the civil rights movement to oppose and justify the criminalization of protest in the present. Media commentators and public officials have decried the Gaza solidarity encampments and other pro-Palestinian protests with comparisons to King and the civil rights movement. King, many liberals and conservatives claim, didn’t inconvenience people, disrupt things, or make people feel unsafe; by contrast, today’s students are portrayed as reckless and dangerous. Students are protesting Israel's brutal war in Gaza and U.S. investment in funding that war. In January the International Court of Justice found that it was "plausible" that Israel was committing genocide in Gaza and in March the U.N. Special Rapporteur determined there were "reasonable grounds to believe that the threshold of genocide...has been met." But two days after the violent NYPD raid, President Biden chastised students—not the police—that “dissent must never lead to disorder.”

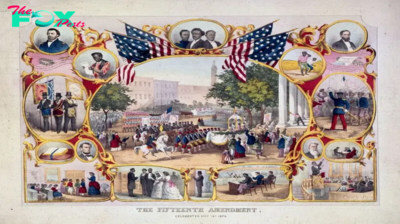

Such popular invocations of the movement miss how the civil rights heroes of the past were viewed as dangerous, disorderly, and unwelcome in their own day. King and others who refused to live by the racial status quo were treated as “extremists” in their time, just like their contemporary counterparts are treated in our time.

Read More: Biden Condemns Campus Unrest Over Israel-Hamas War: 'None of This Is a Peaceful Protest’

Indeed, from the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 on, King understood the need for disruptive protest to upset norms of segregation, poverty, and militarism. And he was criticized for it. Many leaders and commentators chastised King and the bus boycott for hurting the bus company and putting people out of work—and the national NAACP didn’t support the year-long bus boycott, finding it too disruptive, only later taking on the legal case.

Even the march that King would later become most associated with after his assassination–the March on Washington (MOW) on Aug. 28, 1963, of 250,000 people—was not supported by many politicians or most Americans at the time, according a Gallup poll done the week of the march.

Those who opposed civil rights activism were not some Southern fringe. The Chicago Sun Times in 1963 decried the “intimidation” of the MOW. The Chicago Tribune, alongside various Chicago politicians, referred to King as an “outside agitator” when he criticized the city’s deep segregation in 1963, saying it was as bad as Birmingham’s.

As King had said for years: “Racial injustice was not a sectional problem. …De facto segregation of the North was as injurious as the legal segregation of the South.” Indeed, a couple of months before the MOW, on June 12, 1963, Dr. King delivered the commencement address at City College and underscored that point.

Located in the heart of Harlem, City College proclaimed its mission to provide a free excellent higher education to the "whole people" of New York. But in reality, King addressed a nearly all-white crowd of 15,000 people that day. Less than three dozen of the 2,800 students graduating in 1963 were Black, though nearly half of the city’s schools were Black and Puerto Rican. Civil rights advocates, parents, and students had been pointing out the problem for years, including City College’s own Kenneth Clark, a sociologist whose research had been crucial to the Supreme Court’s Brown decision striking down school segregation in 1954.

A month after King’s City College address, Black Brooklynites staged pickets intended to disrupt—and ideally halt—construction work at the Downstate Hospital because construction companies excluded Black workers. Protesters even laid down in front of construction vehicles. Hundreds were arrested day after day.

King supported the confrontational demonstrations, stressing they would end “when the Negro feels he is getting a fair deal in housing and job opportunities.” The police roughed up many of the protesters, so King underlined the need for the federal government to create a special civil rights force to prevent police brutality against protestors (in New York as well as Birmingham). King emphasized the role the police played in maintaining segregation and criminalizing protest across the country. He later referred to New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago as sites of “domestic colonialism,” where police and the courts act as “enforcers.”

The year after his address at City College, Black and white moderates called on King to condemn Brooklyn Congress of Racial Equality’s proposed stall-in. Brooklyn CORE had spent the early 1960s challenging housing segregation, school segregation, and job discrimination, garnering little substantive change. Now they sought to draw attention to the city’s rampant inequality by stalling cars on highways leading to the 1964 World’s Fair to be held at Flushing Meadows—to make it difficult for people to continue to avoid seeing racism and poverty. But King refused to condemn the action.

“We do not need allies who are more devoted to order than to justice,” King explained. “I hear a lot of talk these days about our direct action talk alienating former friends. I would rather feel they are bringing to the surface latent prejudices that are already there. If our direct action programs alienate our friends….they never were really our friends.” Allies are not allies who are more devoted to order than to justice, he argued, as he had in the Letter from a Birmingham Jail the previous year.

Read More: The Problem With Comparing Today's Activists to Martin Luther King Jr.

By 1969, City College was still 91% white; while CUNY’s Brooklyn College was 96% white. Alongside student strikes across the country that accelerated in the wake of Dr. King’s assassination, a massive movement at CUNY crescendoed in the spring of 1969. Student protesters challenged CUNY’s segregation, its nearly-all-white faculty, and a biased curriculum. At City College, students engaged in a two-week occupation of the campus. At Brooklyn College, they took over a faculty meeting, had mass demonstrations, briefly took over buildings, and engaged in minor arson and vandalism. And they faced massive criminalization.

The Brooklyn College administration got an injunction against students congregating on campus and the NYPD raided the homes of 17 Brooklyn College activists who then faced multiple felony charges. The media framed them as Communists and terrorizers, and many city leaders and residents saw them as reckless and dangerous. But many Black and Puerto Rican community members rallied around them, continuing the pressure. And these protests ultimately succeeded in the establishment of Africana and Puerto Rican studies departments, the diversification of the faculty, and open admissions at CUNY.

Fast forward 55 years, universities like CUNY and Columbia now celebrate those activists of old, featuring this activism on their websites and praising them in anniversary celebrations of Africana and Puerto Rican Studies. Yet, university administrations brought the NYPD to violently break up the encampments; Brooklyn College suspended all outdoor activities, and Columbia canceled its commencement.

Such actions and the political leaders who misuse the memory of the civil rights movement and student activism of the past have not learned the needed lessons from this history. The young people of this moment—as they protest the war in Gaza, in the face of significant campus and police repression—are picking up that work.

Jeanne Theoharis is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College and the author of the award-winning The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and the forthcoming King of the North.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

-

History22h ago

History22h agoHow Celebrities Changed America’s Postpartum Depression Narrative

-

History2d ago

History2d agoThe Woman Whose Crusade Gave Today’s Book-Banning Moms a Blueprint

-

History6d ago

History6d agoHow Black Civil War Patriots Should Be Remembered This Veterans Day

-

History1w ago

History1w agoThe Democratic Party Realignment That Empowered Trump

-

History1w ago

History1w agoWhy People Should Stop Comparing the U.S. to Weimar Germany

-

History1w ago

History1w agoFlorida’s History Shows That Crossing Voters on Abortion Has Consequences

-

History1w ago

History1w agoThe 1994 Campaign that Anticipated Trump’s Immigration Stance

-

History1w ago

History1w agoThe Kamala Harris ‘Opportunity Agenda for Black Men’ Might Be Good Politics, But History Reveals It Has Flaws