Education

Births in metro Denver are falling faster than much of the country. Here’s what it means for the future.

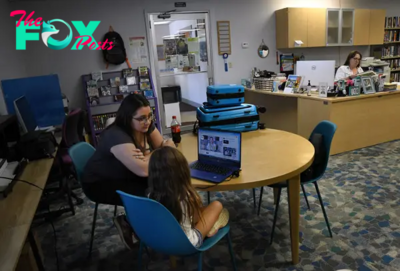

The moment Jordan Alvillar learned about two years into their marriage that her wife no longer wanted to have kids, her life and the future she had long imagined came to a screeching halt.

“It was like you were driving a car full speed toward what you think is going to be your final destination,” Alvillar, 37, said. “All of a sudden someone who’s not you just slams on the brakes. I felt very devastated and it took me a long time to process those feelings.”

Over the next year, as the pair dissected their differences in weekly therapy sessions, that devastation slowly disintegrated. In its place, Alvillar — who discovered she also wanted to live childfree — found a sense of relief.

Freedom, even.

The Denver couple’s decision to pass on having children is one story feeding into a trend of declining birth rates in metro Denver — where the impacts of slowing births have already trickled into classrooms, with smaller numbers of kids showing up to elementary schools.

Denver County experienced the second-largest decline in births among the 100 most populous counties in the country from 2021 to 2022 — the most recent year of county-by-county data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of babies born dropped 6.3%, to 8,649 from 9,232.

Meanwhile, Colorado’s total fertility rate is down, with fewer babies born per woman over her lifetime. Data shows an average of 1.5 births among Colorado women and an average of 1.6 births among women nationally. To fully replace Colorado’s population, the average total fertility rate would have to jump to 2.1, according to Colorado State Demographer Elizabeth Garner.

The freefall in births marks a generational shift and follows birth trajectories of both the U.S. and other developed nations as more millennials choose to have fewer — or no — kids.

Last year, the country’s total fertility rate dropped to 1,616.5 births per 1,000 women, The New York Times reported last week, calling it “a historic low” that is well below the rate needed to maintain the U.S. population. The New York Times also reported in July on the rising number of U.S. adults who say they expect to remain childfree, citing a Pew Research Center study from 2023. Among the results, 47% of adults younger than 50 without kids indicated “they were unlikely ever to have children,” up 10 percentage points since 2018.

Climate anxiety, finances, ratchet anxiety about parenting

Why are adults at a ripe reproduction age opting for childfree households or fewer children than previous generations?

Their answers differ, often driven by deeply personal reasons.

In some cases, distress outside the home alters decisions made inside it. That was especially true during the housing crisis of the Great Recession and the pandemic’s health and economic challenges. Both moments of history spawned a decline in birth rates.

“That instability, that lack of certainty made people feel that they wanted to have fewer children,” Jennifer Reich, a professor of sociology at the University of Colorado Denver, told The Colorado Sun.

The kinds of social support people have access to, including parental leave policies and health insurance, also affect whether they see kids in their future, Reich said, noting that as governments scale back social safety nets, birth rates tend to go down.

At the same time, pressure on parents has been mounting, with parents feeling greater anxiety about their children’s success and an overwhelming sense of responsibility to enroll in high-quality day care, pick the right school and sign up for traveling sports teams.

“Our cultural expectations of what it means to be a good parent keep ratcheting up,” Reich said. The expectation that parents, particularly mothers, invest more in each child “can make parenting feel like more work.”

Other adults want to focus on their Education and careers or find meaning in ways besides having kids. Some feel strapped by student debt, stressed about the worsening effects of climate change or worried about what the country’s future looks like amid sharp political divides, Reich said.

“They’re personal choices,” she said, “but they’re drawing on cultural and social information that help them shape their priorities for their family.”

Much of the overall drop in births has been driven by significant declines in babies born to women under 35, particularly under the age of 25, largely thanks to better access to effective contraceptives, according to Sara Yeatman, a professor of Health and behavioral Sciences at CU Denver.

-

Education20h ago

Education20h agoAnthropology students present their research in poetry, plays and op-eds in this course

-

Education5d ago

Education5d agoStudents with mental health struggles linked to absenteeism and lower grades, showing clear need for more in-school support

-

Education6d ago

Education6d agoPhilly schools are in disrepair − the municipal bond market is 1 big reason

-

Education6d ago

Education6d agoFuture lawyers learn key lessons from studying poetry in parks in this course

-

Education6d ago

Education6d agoHow Ohio schools reduced chronic absenteeism

-

Education1w ago

Education1w ago3 strategies to help college students pick the right major the first time around and avoid some big hassles

-

Education1w ago

Education1w agoThis anthropology course looks at building design from the standpoint of different species

-

Education1w ago

Education1w agoHow to get your kids ready to go back to school without stress − 5 tips from an experienced school counselor