Health

A 15-year-old hockey player with MS may never experience a symptom, thanks to Colorado research

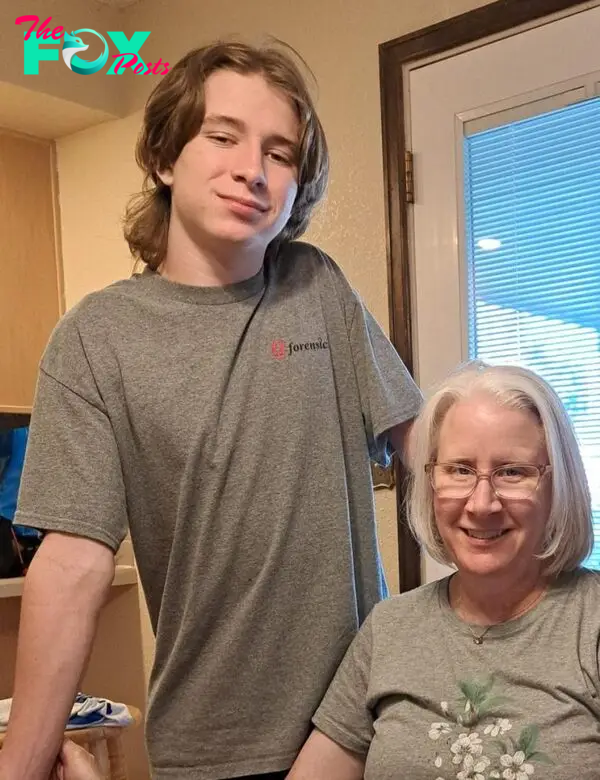

Blaise Pfeifer, 15 and a ninth grader at Standley Lake High School, lives for hockey. He started skating at 3, travels the country for tournaments, and describes gliding across the ice with a puck “like second nature.”

He also knows he has multiple sclerosis, though he has never felt a symptom.

He was diagnosed with the autoimmune disease that attacks the brain and spinal cord after enrolling in a study at Children’s Hospital Colorado for kids whose parents have multiple sclerosis. A series of brain scans beginning when Blaise was 12 revealed neurological activity and lesions that are telltale signs of multiple sclerosis.

Blaise began taking medication, a drug called rituximab, that his doctors say could prevent him from ever getting an MS attack. And since he began taking it two years ago, he has not had any new lesions on his brain.

The sequence of events is remarkable because people do not typically receive a multiple sclerosis diagnosis before they’ve had attacks — legs that go numb, lost vision in one eye that last for a few days, difficulty walking that lasts for a few weeks and then goes away.

There is no genetic test to diagnose MS and no one gene that is identified as the cause. Instead, scientists have identified more than 230 genetic changes that are more common among people who have family members with multiple sclerosis.

Doctors believe the disease, which typically progresses to balance problems and difficulty walking, is caused by a combination of genetics and environmental factors. Low vitamin D, living in a house with a smoker, childhood obesity and contracting the Epstein-Barr virus are among the environmental factors. People are most often diagnosed in their 20s and 30s.

Blaise’s mom, Amanda Pfeifer, was diagnosed in 1996 at age 24, after making four or five trips to urgent care and a hospital emergency department. On her first trips to the doctor, Pfeifer had a numb feeling in her left leg, from the knee to the foot. Doctors speculated that it was a pinched nerve, then poked her with a needle to see if she could feel it. She yelped out in pain, and then they sent her home.

The day Pfeifer woke up with ringing in her ear and numbness in the right side of her face, her father told her to go to the hospital. “That’s when I got my MRI,” said Pfeifer, now 51. “The whole diagnosis took about six months.”

She’s the type of person who goes to the doctor at any sign of a problem, and she has a theory about why women are more likely than men to get diagnosed with MS at a younger age. “That’s because men don’t go to doctors,” Pfeifer said. She knows two men with multiple sclerosis in her hydrotherapy class who told her they ignored symptoms when they were young.

Early diagnosis is key because MS is a degenerative disease, marked by a gradual loss of function that builds over time. Treatment can slow the process.

Pfeifer was adopted and doesn’t know whether her biological parents had MS, so when she heard about the study at Children’s, she didn’t hesitate to enroll her two sons.

“When I was 12, if somebody could have looked at my brian, maybe a lot of what I went through would not have happened,” she said.

Pfeifer has managed her disease with a medication called Tysabri, which works by sticking to cells that are attacking nerves in the brain and spinal cord. The body’s immune system makes cells to kill viruses and bacteria, but with MS, those cells attack the brain and spinal cord by mistake.

The medication is “keeping my MS at bay,” said Pfeifer, who is able to walk with the help of a trekking pole.

“It is what it is”

It was a school day afternoon when Blaise learned his diagnosis. He came to find out that his parents had received a call from the doctor that day. Soon after, the family had a teleHealth appointment with Dr. Teri Schreiner, a pediatric neurologist who specializes in neuroimmunology and the study’s lead pediatric researcher.

“I did take me by surprise,” Blaise said. But right away, he said, his mind shifted to, “What do I do next?”

The news, he said, wasn’t devastating, likely because he has watched his mom function with the disease his whole life. And there was no question that he’d rather know now than find out years from now, when the disease was already affecting his ability to play sports. Blaise is also on his high school lacrosse team, though hockey is his favorite.

“I just took it as face value,” the teenager said. “It is what it is. I’d rather know. If I did wait until I started showing symptoms, it would affect my life quite a bit, for my athletics and just my hockey.”

-

Health13h ago

Health13h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health15h ago

Health15h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health3d ago

Health3d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health6d ago

Health6d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts