Health

How doctors in Denver helped pioneer research on a new drug for food allergies

Carly Edwards found out at just about the worst time possible that her oldest daughter is allergic to eggs.

It was Elsie Jane’s first birthday. And shortly after the birthday girl dived head-first into her smash cake, the allergic reaction hit: hives, vomiting.

“So that was fun for my whole family to watch,” Edwards, who lives in Denver, said. “That was a pretty low moment.”

The birthday revelation kicked off months of trying to understand what had made Elsie Jane sick — while she can tolerate eggs that have been sufficiently baked, it turned out to be egg whites in the frosting that triggered the reaction. Then, once Edwards and her husband learned the parameters of Elsie Jane’s allergy, came the obstacle course of trying to avoid exposure out in the world.

While manufacturers must list common allergens on the label of food sold in stores, eggs can ultimately hide in many things. Restaurant menus can be particularly opaque, and that’s before you consider the risk that bits of egg might accidentally end up in menu items that aren’t supposed to have them.

“We didn’t eat out for a whole year of life because we were so concerned about cross-contamination,” Edwards said.

But a newly authorized treatment could help take the stress out of everyday eating for Elsie Jane and millions of people like her across the country. The federal Food and Drug Administration last month gave approval to a drug called Xolair to help people with certain types of food allergies avoid severe reactions from accidental exposure.

The drug’s approval comes at an especially important time, as the prevalence of food allergies is rising across the country.

Xolair is not a cure for food allergies — it must be taken regularly to remain effective and, even then, it doesn’t allow people with food allergies to eat as much as they like of the thing they’re allergic to. But it can help people avoid the worst when they are accidentally exposed, and that’s a breakthrough.

“It’s almost impossible to avoid reactions and live in the real world,” said Dr. BJ Lanser, a pediatric allergy specialist at National Jewish Health in Denver. “That peace of mind and knowledge of the protection that is there is obviously of significant benefit to many.”

Denver’s fingerprints on the breakthrough

Xolair treats only certain types of food allergies — ones that in medical terms are said to be “IgE-mediated.” That’s the most common type of allergic reaction to food. In simple terms, it means that the presence of a particular food particle causes your immune system to go into attack mode.

☀️ READ MORE

New wetlands, stream oversight proposal surfaces at the Colorado Capitol

Colorado River Basin tribes take harder stance on negotiations about the river’s future

Federal data may be underestimating the number of Coloradans with inadequate internet, report says

The drug works by binding to an antibody called IgE, which triggers the allergic immune response. By tackling IgE and preventing it from binding to receptors, the drug stops the allergic reaction from flaring up.

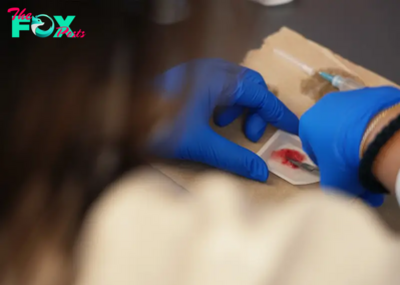

Xolair, which is injected once every two to four weeks, is not a new medicine. It has previously been approved to treat certain types of asthma.

But the idea of using an anti-IgE drug on food allergies isn’t new either — in fact, it has roots in research first conducted at National Jewish and its predecessors.

A husband-wife team of researchers working in the 1960s at the Children’s Asthma Research Institute and Hospital in Denver were among the first in the world to discover IgE.

Roughly 35 years later, National Jewish researchers led by Dr. Donald Leung studied the use of an anti-IgE drug to treat peanut allergies. The results of the study were so promising that Leung and his colleagues concluded the drug “should translate into protection against most unintended ingestions of peanuts.”

But Leung said the vagaries of pharmaceutical development and federal regulatory approval ultimately meant the research didn’t go anywhere right away. At the time, in the early-2000s, food allergies were also less common.

“Food allergy is a relatively new problem when you look at it in terms of history,” Leung said.

Still, Leung and his National Jewish colleagues didn’t give up and continued to study the origins of food allergies. (Among his research interests is examining the connection between food allergies and skin conditions like eczema.)

-

Health1h ago

Health1h agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health3h ago

Health3h agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health18h ago

Health18h agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoCOVID-19’s Surprising Effect on Cancer

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoWhat to Know About How Lupus Affects Weight

-

Health5d ago

Health5d agoPeople Aren’t Sure About Having Kids. She Helps Them Decide

-

Health5d ago

Health5d agoFYI: People Don’t Like When You Abbreviate Texts