Entertainment

A considerate staging and fantastic efficiency of Mozart’s Lucio Silla in Salzburg – Seen and Heard Worldwide

Austria Mozart, Lucio Silla: Soloists, Refrain of the Salzburg Landestheater, Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra / Carlo Benedetti Cimento (conductor). Salzburg Landestheater, 4.6.2024. (MB)

Austria Mozart, Lucio Silla: Soloists, Refrain of the Salzburg Landestheater, Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra / Carlo Benedetti Cimento (conductor). Salzburg Landestheater, 4.6.2024. (MB)

Manufacturing:

Director – Amélie Niermeyer

Set designs – Stefanie Seitz

Costumes – Kathrin Brandstätter

Lighting – Tobias Löffler

Video – Janosch Abel

Dramaturgy – Frank Max Müller and Vinda Miguna

Refrain director – Tobias Meichsner

Forged:

Lucio Silla – Luke Sinclair

Cecilio – Katie Coventry

Giunia – Nina Solodovnikova

Lucio Cinna – Nicolò Balducci

Celia – Anita Rosati

Aufidio – Joseph Doody

The Salzburg Landestheater’s new manufacturing of Lucio Silla, typically accorded the best of Mozart’s three opere serie for Milan, was first seen in January of this yr. Although I used to be really in Salzburg for the second efficiency, I used to be unable to see it then, so I used to be delighted to have alternative to meet up with a considerate staging and fantastic performances, worthy of anybody’s consideration — and which it will be extremely fascinating, if in any respect doable, to have preserved on movie. The sixteen-year-old composer’s relish for the forces, refrain included, at his disposal in Milan was vividly delivered to life. If he had not but realized the dramatic virtues, at the least every so often, of concision corresponding to one experiences in later dramas, it’s troublesome to think about anybody having minded. Such was the experience with which this younger forged made Mozart’s recitative and da capo arias, coloratura particularly, vividly significant in addition to vocally thrilling, that extra trendy prejudices in opposition to the style have been totally dispelled. The standard of staging and performances additionally provided a welcome alternative to (re-)assess Giovanni De Gamerra’s admittedly very early libretto.

De Gamerra has are available in for a nasty press, then and now: to my thoughts, at the least a little bit unjustly. Lorenzo Da Ponte, who maybe, having been compelled to depart Vienna, had his personal causes for dissatisfaction with those that had remained, reported in a footnote to his memoirs:

Leopold [II, Holy Roman Emperor] took [Giovanni] Bertati to his opera. A yr later got here [Giovanni Battista] Casti: and that wretched dramatic cobbler was dismissed. However Casti was not keen on arduous work. He requested for an assistant and obtained one in individual of Signor Gamerra, a poet well-known for his Corneide, a poem in seven or eight fats tomes whereby he talked about all of the horns that had appeared in Heaven or on earth from the start of Vulcan all the way down to these of his personal grandfather. This ungrateful cornifex had not been a yr in Vienna earlier than he started butting together with his benefactor, accusing him of Jacobinism; and poor Casti … was enjoined to depart from Vienna directly.

That is each odd and intriguing, provided that Leopold himself spoke harshly of the poet, advising his brother Ferdinand, governor of the Duchy of Milan, in a letter John A. Rice found within the Vienna archives, that De Gamerra was ‘fanatic to extra, hot-headed, imprudent regarding … liberty, very harmful,’ a startling excessive judgement coming from one who was removed from reactionary, and which definitely attests to robust political sentiments on De Gamerra’s half. We would additionally be aware, although, that Leopold was none too complimentary about Ferdinand, dismissing him in a secret memorandum on members of his household (!) as ‘a really weak man, of little mind and paltry expertise, however who has a really excessive opinion of himself’. Make of that what you’ll. (I shall resist the temptation to enter better element concerning the Home of Austria and Mozart’s operas right here, however extra will observe each in articles and, when completed, a e book on the whole operatic œuvre.)

Maybe extra vital has been the view that the libretto, particularly its ending, will not be superb. Mozart discovered himself having to make revisions in mild of criticism (of the libretto) by Metastasio. In his New Grove article, Julian Rushton calls the denouement ‘unconvincing’ and the libretto as a complete ‘turgid’, while permitting Lucio Silla nonetheless to be ‘musically the best work Mozart wrote in Italy, … [ranking] with opera seria by the best masters of the time’. I definitely mustn’t dissent from the latter, both in precept or in mild of this efficiency, however I discover the judgement of the libretto unduly harsh, each basically and with respect to the ending, demanded by the conventions of the style but additionally foreshadowed greater than many permit each in libretto and rating. A advantage of Amélie Niermeyer’s manufacturing is its taking the ‘drawback’ of the ending, on which extra shortly, on board. Larger religion within the work, one may effectively argue, may make such a method pointless; however in mild of the selections made, cheap and justified for a recent manufacturing, its subversion (or, should you desire, extension) makes good sense.

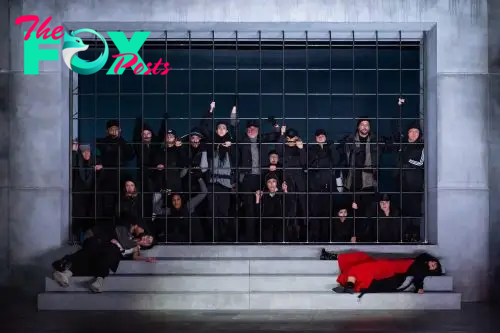

Neirmeyer takes her depart from the historic Lucius Sulla’s dictatorship. That didn’t essentially maintain fairly the identical implications as now, however such qualification is essentially irrelevant if it makes for good drama, which, on the entire, it does. On this world of contemporary dictatorship, rebels, resisting a brand new, brutal régime, during which opponents, pictured in placards held up by these resisting, have been ‘disappeared’. Lucio Silla exists and is amplified by propaganda, photographed snaps retouched and enhanced by his pal, the tribune Aufidio to painting the essence of robust, masculine management. Cecilio, Lucio Cinna and others are in hiding, clothes suggestive of a guerilla motion, and crucially are being watched (at the least a part of the time) by means of digital surveillance from the dictator’s palace.

Silla vacillates and is persuadable, choosing up on the mediating position of his sister Celia in addition to his love for Giunia, she of the outdated regime, in order that his sudden determination for clemency (a recurring theme, we’d be aware, by means of Mozart’s total œuvre, in addition to a lot different eighteenth-century opera) appears much less unmotivated than has been alleged. However there’s a twist. Since we’ve got moved to a world of contemporary psychological realism, inheritor to the ‘Romantic essential custom’ Rice highlighted as having completed such harm to understanding of the composer’s remaining instantiation of operatic clemency, La clemenza di Tito, the change of coronary heart is a ruse. The dictator who, it has appeared, may desire a prolonged retirement during which he can indulge himself with whisky and girls, has had a plan all alongside. Acclaimed by the folks for forgiveness of those that have plotted in opposition to him, he has in truth seized the second so as to add them to the ranks of the disappeared, chillingly undercutting the ultimate vocal and orchestral rejoicing, while, in a way, remaining true to the claims to complete data on which clemency insists. (Consider Sarastro in addition to Tito.) If, generally, the relentless exercise throughout arias threatened to detract from moments of musical reflection, it was a finely balanced factor. Mozart survived — and somewhat greater than that. If something, the traditional AMOR/ROMA battle gained by its rethinking.

Luke Sinclair’s efficiency within the title position was basic to this dramatic success. Vocally robust and agile, his stage portrayal helped fill in most of the gaps. Ably assisted by Joseph Doody as Aufidio, no imply singer and actor himself, Sinclair’s Silla provided psychological depth in instability, while sustaining one thing fairly different to the exterior world. These in whom he nearly met his match have been equally spectacular, complementing and contrasting like a fantastic wind ensemble. Katie Coventry as Cecilio provided an in depth vary of dramatic color, not completely not like an early piano. Nicolò Balducci’s coloratura and the dramatic use he put to it within the soprano castrato position of Cinna would have greater than satisfied even essentially the most countertenor-sceptical of listeners. Nina Solodovnikova’s warmly sympathetic, but unswervingly dedicated Giunia introduced her music and position thrillingly to dramatic life, poignantly in tandem with the spirit world (and others) conjured up by Carlo Benedetti Cimento and the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra, in addition to the Refrain of the Salzburg Landestheater. Anita Rosati’s Celia proved a musical in addition to dramatic lynchpin, stylistic command second to none. However then, I might nearly have exchanged the descriptions given for every singer at will. All had merciless vocal calls for positioned upon them, all succeeded not solely in fulfilling them, however in creating an ensemble drama that was excess of the sum of its elements.

Cimento’s alert musical management from the pit, allied to the lengthy Mozartian expertise of the orchestra, was simply as spectacular — and essential. Tempo selections have been clever. Dramatic momentum was created and maintained. Artists on stage got freedom to behave as singing actors, nonetheless sure collectively by cautious ensemble preparation and finely judged orchestral incitement. Affective use of keys, E-flat main particularly, was meaningfully conveyed. That’s Mozart’s doing within the first occasion, after all, but it nonetheless wants – and obtained – delicate, dramatically alert conducting and orchestral efficiency. Likewise, the composer’s extraordinary orchestration, veiled, muted strings, tender woodwind, sepulchral trombones and all, disconcerted, beguiled, and thrilled.

A welcome and apt shock got here at the start of the second half (the third act) when an entr’acte not one million miles away from Mozart, however which I didn’t recognise and which I used to be 99.5% positive was not Mozart, was heard. I later found that it was the primary a part of the second motion and the entire third from Johann Christian Bach’s Symphony in G minor, Op.6 No.6. Not solely did it accompany the pantomime motion very effectively; it served to remind us each of Mozart’s shut connection to the ‘London Bach’ and the latter’s personal Mannheim Lucio Silla, to a revised (I admit, improved) model by Mattio Verazi of De Gamerra’s libretto. Maybe Salzburg may deal with this subsequent? It might be a fantastic factor certainly to have the ability to see and listen to the 2 collectively someday. Within the meantime, this did properly certainly.

Mark Berry

-

Entertainment3h ago

Entertainment3h agoClassic Korean Movies Like Piagol to Add to Your Watch List

-

Entertainment3h ago

Entertainment3h agoOver 60 Million People Tuned in to Watch Jake Paul vs. Mike Tyson

-

Entertainment10h ago

Entertainment10h agoPopular Hudson Valley Italian Restaurant Addresses Closing Rumors

-

Entertainment11h ago

Entertainment11h agoRHOBH’s Dorit Kemsley Addresses Viral Smoking Scene on Season 14 Premiere: ‘I Was Being Chased’

-

Entertainment14h ago

Entertainment14h agoThe 10 Best Podcasts of 2024

-

Entertainment16h ago

Entertainment16h ago‘RHOBH’ Star Dorit Kemsley Opens Up About Crumbling Marriage to PK: ‘Agreed to Separate’

-

Entertainment1d ago

Entertainment1d agoReview: Disney’s New TV show Interior Chinatown is a Satirical Take on Theatrics

-

Entertainment1d ago

Entertainment1d agoPrestige Exclusive: Ronny Chieng and Chloe Bennet Talk Interior Chinatown and Representation