Health

Ian Fleming: A Life Incomplete

The Man with the Golden Gun was my first encounter with James Bond. It was a birthday treat to the cinema to witness the world’s most popular state-sponsored murderer in celluloid action. I’m not sure if it was the gratuitous killing, the pantomime villains, the gadgets or the fantasy women that floated my boat, or the whole larger-than-life shooting match. But hooked I was and, in a desperate desire to satiate a craving for more tall tales from the inner lining of the Iron Curtain, turned to the novels and Bond’s creator Ian Fleming.

Since consuming all 14 of the highly quotable books (12 novels and two short stories) in my teens, movie Bond has shadowed me. I interviewed Roger Moore for the anniversary of Bond’s 50th and wrestled with the staggeringly awkward Goldfinger Aston Martin DB5 at Beaulieu in England, some years later. Much like the women in Bond’s life, Fleming’s lexicon was an on-off lover. I was alerted to Nicholas Shakespeare’s biography of Fleming, The Complete Man, through a colleague in Hong Kong, who’d also shared a similar journey to my own – through “paper Bond”. He loved it and raved about it. As did I, when my copy arrived in late 2023. Skip forward six months and I’m sitting in the interview room at Clarks Amer in Jaipur, Rajasthan. The hotel is home to the Jaipur Literature Festival and Shakespeare has The Complete Man on tour and is happy to discuss four and a half years of access to the Fleming archive.

When I meet Shakespeare he’s upbeat, having come directly from a one-on-one stage discussion with Matthew Parker, the author of Goldeneye (named after Fleming’s Jamaican bolthole). He’s played to a packed house and has just left the stage having destroyed some young TV hot blood who was stupid enough to enquire as to “Fleming’s favourite movie Bond”.

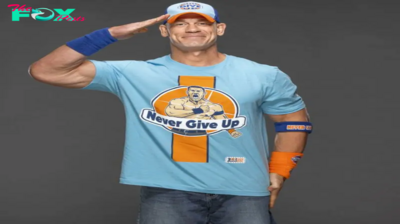

Ian Fleming’s biographer, Nicholas Shakespeare

We laugh about this as we take seats and coffee in the buzzing press room, and I tell him his answer is like a stiletto knife from Rosa Klebb. “Well, Fleming only met Sean bloody Connery before he died. I mean, do your homework,” he barks back. I’m glad I have. And the man who dresses like an English college professor, perspiring in the desert sun, settles back.

The book itself is painstakingly researched, as comprehensive a look at 007’s creator as has ever been put pen to paper. Fleming himself was a complicated character, born of a family with no middle margin. A grandfather from the textile mills of Dundee in Scotland, who made good. So good, Fleming was raised to colossal wealth in a huge 44-bedroom estate bedded on the fringes of London.

But for all the new money, Fleming’s formative years were dismal. Aged eight, he lost his father to the Great War and, unsurprisingly, everything spiralled. It didn’t help that he had to walk in his brother’s ever-growing shadow. If Peter Fleming broke records at Eton, then Ian scratched them. He’s requested to leave a term early at Eton and similarly a dose of gonorrhoea marches him out of Sandhurst a little while later. He fares no better on civvy street; a spectacular failure as a stockbroker and rejected for a role in the Foreign Office – quite some feat given the circles in which his family walked and talked. Shakespeare acknowledges that to all intents Fleming’s career was toast. And then a little thing called the Second World War reared its head.

“He wasn’t a black sheep, probably shades of grey. And yes, outside of reporting for Reuters, Ian was a disaster. But he loved the whole quickness of the news process, the precision of sentence and accuracy. And it was for this reason he was chosen in 1939 by Admiral Godfrey, head of naval intelligence, to be his personal assistant. Godfrey was looking for a man who was left-field, who knew about banking – albeit badly – and who knew about journalism. And Fleming ticked all the boxes.

“Godfrey kind of hands over the task of naval intelligence to Fleming. Well, what intelligence, as the entire fleet was at sea? But, Fleming indirectly reports to Churchill, who was First Sea Lord, and Churchill had been a great friend of his father, had even written his father’s obituary in The Times, and Fleming almost worshipped Churchill. And he rewrites speeches and memos, and he’s encouraged to use his imagination. That same imagination that got him into so much trouble, now he thrives on. He’s given access to every intelligence department, and he’s got his finger on every single intelligence power. It’s a defining moment – and if anyone had a ‘good war’, it was Fleming.”

Unbeknown to Fleming, this would be the birth of James Bond. I ask Shakespeare to elaborate. He doesn’t need persuasion, and as agent to the archive of the world’s best spy, he throttles the query. Now he has a look of the bastard child of Boris Johnson, and Bond nemesis Karl Stromberg (The Spy Who Loved Me), to him. The Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature has shark’s teeth. He’s half monk, half hitman.

“He’s so much more important than his fellow intelligence novelists, like Graham Greene or John Le Carré, who were minor fringes in intelligence. Le Carré was a tiny cog in Hamburg, compared with Fleming, who was in the inner sanctum of British intelligence. He and his brother were two of only 30 people who were Ultra-cleared in April 1940 [Shakespeare is referring here to the top-secret wartime method of breaking of encrypted German military signals].”

Bond novels in various languages on display at the Imperial War Museum in London

First editions of early Bond novels

The Le Carré subject draws me in, as I recall the George Smiley author had little time for Fleming – which, considering his clout in the intelligence network, seems rather odd. “Le Carré was a very comPetitive person anyway, and most writers want to be the only writer on set at a bookshop, and I think Le Carré always felt that Bond was more famous than Smiley. So, when you think of Le Carré now, you think of Le Carré before you think of Smiley, but the problem is with Fleming, you think of Bond before you think of Fleming. So, Le Carré was able to keep his own image but was never able to trump Bond with Smiley. He used to pinch all the actors: he pinched Connery and [Piers] Brosnan and he wanted to add Daniel Craig to star in the rewrite of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. I did the last session with Le Carré in public, and I talked about this. It’s interesting because both men were quite fluent in German, they’re both spooks. Both leave their private school early, they both go to Switzerland, they both join the intelligence service, they both marry as their first wife a woman called Anne, and they both write their breakthrough novel in just eight weeks.”

Fleming’s Casino Royale was written (like all the Bond novels) in Jamaica at Goldeneye and at breakneck speed. Ian’s time in intelligence and international journalism had granted him access to characters and capers that, while larger than life, were generally born of real events and people. We touch on the importance of Jamaica to Fleming.

“You know, if he’d have been in Swindon or anywhere else, I don’t think Bond would have existed. Because I think it was the Goldeneye set-up with two months holiday that allowed Bond to come into creation. But the books themselves didn’t sell too well at the outset. We’re talking small print orders and sales of three or four thousand copies.

“And by the time of his death, there’s something like 30 million copies have been sold of his books, and they’re translated into 18 languages. I think he’s got a very good product to begin with and within that he knows how to write. Pace is very important for him. He wanted you to turn the pages and he’s still got all these stories from the Second World War, and he can pretend it’s against the Russians. So, by the time he’s written his fifth book, From Russia with Love, he goes to Jamaica and he tells his publisher, this is my last Bond. And what happens then? The Suez Crisis. So, he’s rescued with material to write about that’s new and then gets this huge slab of luck.”

Speaking of luck and Fleming, I ask Shakespeare if it’s true that Fleming met the Kennedys and how this extraordinary chance happening came about. “Oh, absolutely it’s true. So, Bond starts to rise from the same waters as Antony Eden sinks and as the sun continues to set lower on the British Empire, Bond becomes this one-man saviour on whom the world relies, and this puts Fleming on the front pages of the newspapers. Now, he’s well-known in Britain but then he has spectacularly good luck in the United States. This is my favourite chapter in the book, and I nearly began the book with this. It’s his meeting with John F Kennedy in March 1960. Six months from now, Kennedy is going to be elected president and Fleming meets him in Georgetown, DC, through a friend.”

“There’s Jack and Jackie Kennedy coming from Trinity Church and the friend, who knows the Kennedys, shouts over that they have Ian Fleming in the car. Jack Kennedy leans his head through the window and says: ‘What, you mean James Bond?’ It turns out Kennedy has read all the books and become a complete passionate Bond fan. So, that night Fleming’s invited to dinner. There are only six people there and an extraordinary conversation takes place after dinner where Kennedy, vexed by what’s happening in Cuba with Castro, turns to Fleming and asks what James Bond would do about Castro. And all this up until now, I think, has been the nice kind of gossipy conversation that’s been reported – but what Kennedy is actually saying is what would Ian Fleming do about Cuba? Equally important, though, is the fact that the Kennedys – and the soon-to-be-President of the United States – endorsed Bond. Not surprisingly, sales on the other side of The Pond rocketed.”

It’s a remarkable episode that’s as astonishing as any of Bond’s exploits of derring-do. But time has marched on, and I can see that Shakespeare’s PR is starting to get jumpy about how long we’ve been chatting. I acknowledge her and mouth silently for a couple more minutes. Shakespeare nods and I ask him, after being so close to all Fleming’s private records, letters and diaries, what does he really think of 007’s creator? Shakespeare sits silent for a moment, as if unsure of the answer himself. His response is cathartic.

Fleming at his desk in Goldeneye

Fleming (right) with actors Sean Connery and Shirley Eaton on the set of Goldfinger

British author and creator of James Bond, Ian Fleming

“Monique, who Fleming was going to marry, had a son who I was in contact with. The son sent me the photograph that Fleming had given Monique when he was 23 that she had on her desk until the end of her life. I put it on my desk for four years, and for four years I just looked at him and I just didn’t get him. He just looked like an arrogant old man. Right at the end I suddenly did think I understood him more, and I was much more sympathetic to him. We’d have probably been able to talk, and I would have possibly liked him. I’m hard on him. It’s a tragic life. I mean, I feel sorry for him. He dies young. He lost his father young. He’s kind of ill, in an unhappy marriage and success comes when it’s too late. That surely must have affected his ability to emotionally attach. I don’t think his was a happy life. He’s ultimately successful, but what is success?”

As I stand to leave and bid Shakespeare farewell, I’m struck again by the title of the book The Complete Man. Certainly, Mr James Bond could live up to that monicker. But, Fleming, no. The only time in his life when he felt “complete” was during wartime and one of the planet’s most deadly and atrocious periods in its History. A time when his work was to deal out, and deal in death. It helped craft Bond, but once the coNFLict was over, Fleming was lost. A shadow of a man and all rather incomplete.

-

Health5h ago

Health5h agoTeens Are Stuck on Their Screens. Here’s How to Protect Them

-

Health10h ago

Health10h agoHow Pulmonary Rehab Can Help Improve Asthma Symptoms

-

Health10h ago

Health10h ago10 Things to Say When Someone Asks Why You’re Still Single

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoThe Surprising Benefits of Talking Out Loud to Yourself

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoDoctor’s bills often come with sticker shock for patients − but health insurance could be reinvented to provide costs upfront

-

Health1d ago

Health1d agoHow Colorado is trying to make the High Line Canal a place for everyone — not just the wealthy

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoWhat an HPV Diagnosis Really Means

-

Health2d ago

Health2d agoThere’s an E. Coli Outbreak in Organic Carrots